01/07/18 (written by David A. Shirk) — Late on the afternoon of Saturday, December 9, 2017, Jose Santos Hernández, the mayor of the town of San Pedro el Alto, Oaxaca, was assassinated. The town is known for its internationally recognized forestry management program and recent damage from Mexico’s September 2017 earthquakes than as a place for drug trafficking. Santos Hernández’s murder took place on an unpaved road near the 175 highway, as the mayor and his family were returning from a religious festival celebrating the Virgen de Juquila in the town of Santa Catarina Juquila. Santos Hernández was forced from his car and fatally wounded by several gunshot wounds, including a close range shot to the head.

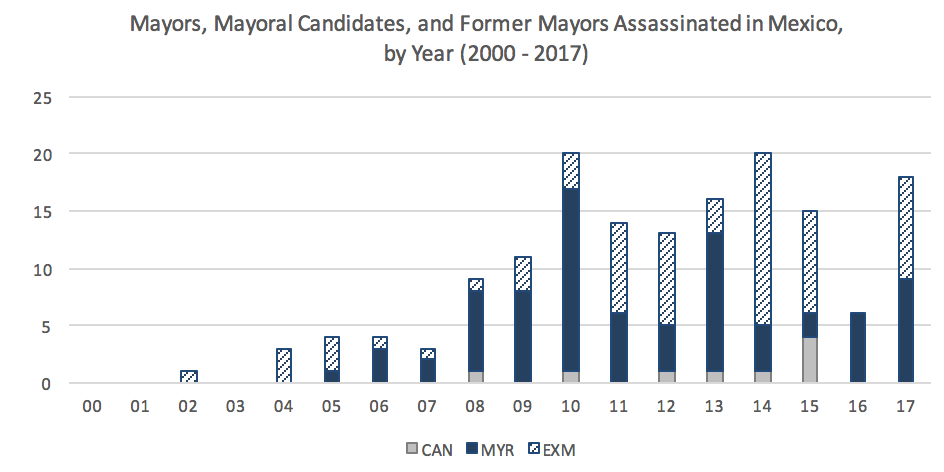

According to a new Justice in Mexico working paper entitled “An Analysis of Mayoral Assassinations in Mexico, 2000-17″ by Laura Y. Calderón, Santos Hernández was among the nine mayors killed in 2017, including three in December 2017 alone. All told, Calderón found that at least 78 mayors have been assassinated since the year 2000 and taking into consideration candidates and former officials, more than 150 of Mexico’s mayors have been killed in the past fifteen years (See Figure 1). Using comparable data from 2016, Calderón finds that Mexico’s mayors are three times more likely to be killed than journalists in Mexico, and 12 times more likely to be killed than the average person in Mexico. Her findings raise serious concerns about the dangers facing the country’s local politicians, particularly as Mexico looks to an important election year in 2018.

According to Calderón, since 2000 there has been an unprecedented number of assassinations targeting current, former, and aspiring local elected officials in Mexico. Drawing on information from Memoria, a database of individual homicides in Mexico compiled and managed by the Justice in Mexico program at the University of San Diego, Calderón examined all 156 assassinations involving sitting mayors, former mayors, and candidates for mayoral office in Mexico’s 2,435 municipal governments. In total, the Memoria dataset identifies 79 mayors, 68 former-mayors, and 9 mayoral candidates that have been murdered under various circumstances.

Calderón’s study underscores Mexico’s alarming rate violence targeting local officials, and illuminates a number of interesting trends related to mayoral assassinations. Drawing on the Memoria dataset, Calderón identifies a former PRI mayor from the state of Tamaulipas, who was shot in 2002, as the first victim of violence targeting mayors, former-mayors, and mayoral candidates. In 2005, for the first time in decades, a sitting mayor was assassinated in the town of Buenavista Tomatlán, located in the state of Michoacán.

This was followed by a dramatic increase in the number of assassinations targeting mayors, mayoral candidates, and former mayors as Mexico experienced a major increase in drug-related and other criminal violence starting in 2008. Calderón points out that some mayoral killings appear to have patterns associated with drug production and trafficking activities. For example, mayors assassinated in smaller towns tend to be located in rural areas well suited to drug production and transit. Those assassinated in larger cities tend to be located closer to the U.S.-Mexico border, which serves as an important transshipment point for drugs headed to the U.S. market.

Indeed, Mayor Santos Hernández was killed the rural mountain town of San Pedro el Alto, located in a region—the “Costa Chica” located on the southwestern portion of the Oaxacan coast between the resort cities of Acapulco and Puerto Escondido—known as a trans-shipment point for drugs smuggled in small vessels. In recent years, farmers and fishermen in the Costa Chica region have been threatened or harmed by drug trafficking organizations, and there have been reports of criminal organizations engaged in public shootouts.

However, it is not clear that the motive of Santos Hernández’s murder was attributable to organized crime. On Thursday, January 11, authorities arrested the city treasurer of San Pedro El Alto, Francisco Javier, for being the alleged intellectual author of the murder. Local investigators arrested a man identified in newspaper reports as “Francisco Javier,” the treasurer of the local government, who authorities believe to have orchestrated the attack on Mayor Santos Hernández as a result of a feud over local financial matters. The matter remains under investigation.

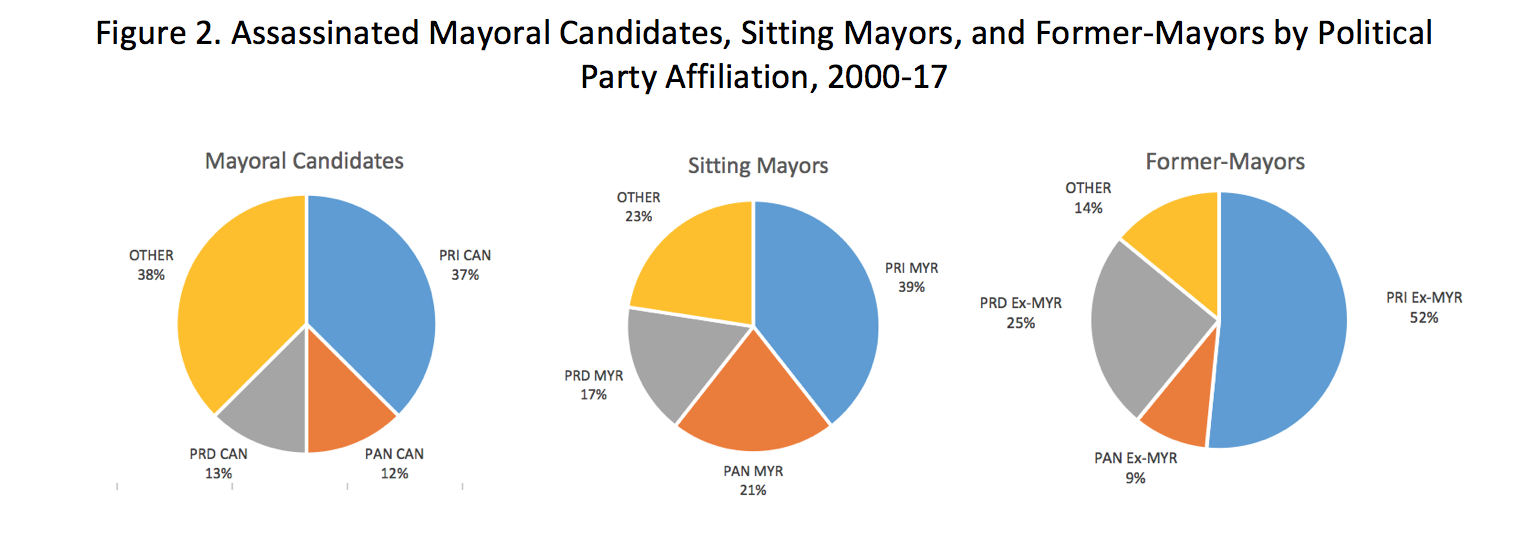

Mayor Santos Hernández’s murder underscores that many factors can play into violence targeting local officials. For example, according to Calderón, the assassination of local politicians has affected all three of Mexico’s major parties, as well as a number of smaller parties. While mayors from the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) head roughly 60% of Mexico’s local governments, they represented only 37% of those mayoral candidates and 39% of sitting mayors that have been assassinated in recent years. Although the number of mayoral candidates assassinated was fairly small (9 total), three were candidates from Mexico’s leftist fringe parties, including the Movement for National Renovation (Morena), the Social Democratic Alternative (ASD), and the Partido Único (PUP).

Meanwhile, among the 71 sitting mayors killed, 21% were from the National Action Party (PAN), 17% were from the Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD), and the remaining 23% were from smaller third parties. Partly because of its historically dominant role in Mexican politics, a much greater share of assassinated former-mayors heralded from the PRI (52%), while the next largest shares came from the PRD (25%) and smaller third parties (14%); a relatively smaller share of former PAN mayors (9%) have been killed after leaving office. A 2016 article by Beatriz Magaloni and Zaira Razu suggests that PAN officials at the state and local level may have been insulated from violence through better coordination with the federal government as violence spiked during the government of President Felipe Calderón (2006-12), a member of the PAN.

What is clear is that local authorities have taken the brunt of violent attacks against public officials since the start of a decade-long, nationwide surge in homicides. A 2015 study by Guilermo Trejo and Sandra Ley analyzed roughly 500 violent threats and attacks against local politicians in Mexico and found that the vast majority involved local officials (83%) and that most occurred between 2007 and 2014 (90%).

As Santos Hernández’s case appears to illustrate, many local politicians are assassinated for complex reasons seemingly unrelated to organized crime, including political rivalries, inter-personal conflicts, and intra-familial violence. Also, as Calderón’s study reveals by including former-mayors in her analysis, a large number of former government officials are also targeted for violence, presumably well after they are of strategic value to criminal organizations. This raises important questions that require further investigation into the motives and incentives behind the murders of Mexico’s former mayors.

What is quite certain is that the recent wave of violence against local officials is unprecedented in Mexico, and has few parallels elsewhere. Recent trends also underscore the precarious situation for current aspirants to local elected office as Mexico gears up for the 2018 elections. One of the front runners in this year’s presidential election is Andres Manuel López Obrador, a former member of the PRD who defected to found Morena, a new leftist party that has gained ground rapidly in recent years. The prospect of a Lopez Obrador victory has heightened political tensions and could contribute to recent patterns of violence targeting local candidates and officials.

SOURCES:

Raul Laguna, “Lío de dinero motivó crimen de presidente municipal de San Pedro El Alto,” El Imparcial de Oaxaca, December 12, 2018. http://imparcialoaxaca.mx/policiaca/110247/lio-de-dinero-motivo-crimen-de-presidente/

“Asesinan a alcalde mexicano de San José Alto, Oaxaca,” Telesur, December 9, 2017, https://www.telesurtv.net/news/Asesinan-a-alcalde-mexicano-de-San-Jose-Alto-Oaxaca-20171209-0022.html

Darwin Sandoval, “Matan a president municipal de San Pedro El Alto, Pochutla, Oaxaca,” El Imparcial de la Costa, December 9, 2017. http://imparcialoaxaca.mx/policiaca/96409/matan-a-presidente-municipal-de-san-pedro-el-alto-pochutla-oaxaca/

Patricia Briseño, “Ejecutan a tiros al alcalde de San Pedro El Alto, Oaxaca,” Excelsior, December 8, 2017. http://www.excelsior.com.mx/nacional/2017/12/08/1206643

Juan Carlos Zavala, “Asesinan a presidente municipal de San Pedro El Alto, Oaxaca,” El Universal, December 8, 2017. http://www.eluniversal.com.mx/estados/asesinan-presidente-municipal-de-san-pedro-el-alto-oaxaca

Archivaldo García, “Incomunicado San Pedro el Alto, Oaxaca; viviendas dañadas,” October 3, 2017, El Imparcial, http://imparcialoaxaca.mx/costa/65167/incomunicado-san-pedro-el-alto-oaxaca-viviendas-danadas

Beatriz Magaloni and Zaira Razu, “Mexico in the Grip of Violence,” Current History, February 2016, p. 57-62. http://www.currenthistory.com/MAGALONI_RAZU_CurrentHistory.pdf

Guillermo Trejo y Sandra Ley, “Municipios bajo fuego (1995-2014),” Nexos, February 1, 2015. https://www.nexos.com.mx/?p=24024

Ernesto Martínez Elorriaga, “Hallan el cuerpo de ex edil michoacano secuestrado la mañana del jueves,” La Jornada, May 10, 2008, http://www.jornada.unam.mx/2008/05/10/index.php?section=estados&article=026n1est