12/05/17 (written by Lucy Clement La Rosa) – The antithesis of democracy and good governance, corruption has repeatedly undermined development in Latin America and the Caribbean. Over recent years, the region has endured numerous corruption scandals; most recently, Colombia’s oil refinery embezzlement and Brazil’s Odebrecht scandal exposed the magnitude of political graft and crony capitalism. The multifariousness of corruption undermines the crucial building-blocks of society, including access to information, human rights protections, political processes, judicial institutions, and economic policies.

Although the recent exposure and prosecution of corruption schemes across Latin America has stimulated regional dialogue on rule of law, public assessment of countries’ anti-corruption capacity remains perturbingly low. According to Transparency International’s latest Global Corruption Barometer, People and Corruption: Latin America and the Caribbean, corruption is on an upward trend. An average of 62% of over 22,000 Latin American constituents answered that the level of corruption in their respective country has increased since 2015. Moreover, 53% of the survey participants answered that their country’s government is poorly addressing the problem of corruption. The civil functionaries identified by the public as the most corrupt were elected officials and law enforcement agents, both indispensable to rule of law (Transparency International).

However, in this case, bad news may be good news. The regional spotlight on perpetrators of corruption has stimulated public discourse and action; as Latin American countries increasingly acknowledge institutional voids in governance, the stage is set for reform. Notwithstanding, regional cooperation and anti-corruption capacity building will be essential in addressing the demands for transparency and accountability.

Mexico has especially felt the cancer of corruption with malignancies across economic and political sectors. According to a 2015 report by the Mexican Institute for Competitiveness corruption costs Mexico about 9% of its annual Gross Domestic Product (Instituto Mexicano para la Competitividad, A. C.). Aside from draining Mexico’s pocketbooks, corruption has contributed to an increasingly disenchanted populous. Pew Research Center, identified Mexico’s top public concerns in 2017: crime, corrupt political leaders, and corrupt police officers. In a comparison between 2015 and 2017, these concerns have increased respectively by 10%, 12%, and 9% (Pew Research Center). Moreover, Transparency International identified Mexico’s bribery rate as the highest in the region with 51% of the populace paying a bribe for public services in the past 12 months, followed by the Dominican Republic and Peru with 46% and 39%, respectively (Transparency International).

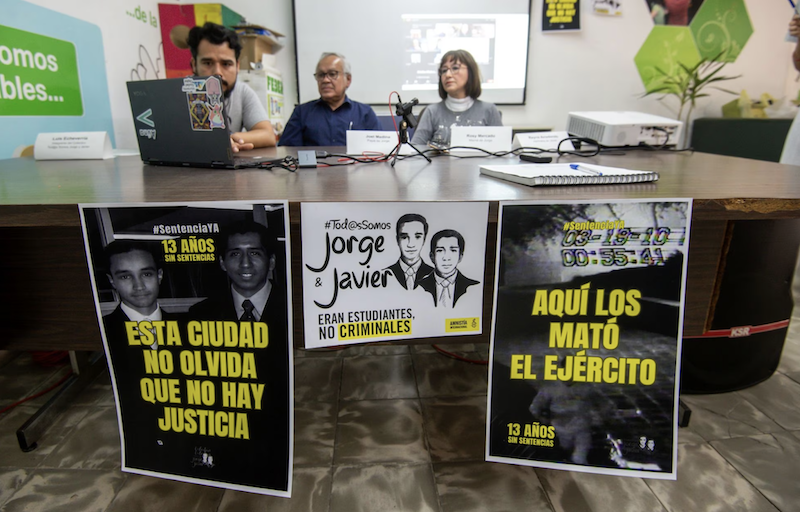

Highly publicized corruption scandals have only added fuel to the fire: including but not limited to, the massacre of 43 students and protestors from Ayotzinapa, Guerrero; the extended manhunt for the former governor of Veracruz, Javier Duarte, on charges of political graft and organized crime; the government surveillance spyware allegedly targeting a variety of high-profile human rights lawyers, anti-corruption activists and journalists; and allegations of negligence in the seismic wake of destruction following two earthquakes in September of 2017.

In response, the public voice in Mexico has increasingly clamored for transparency and accountability. The galvanized public paved the way for the creation of a National Anti-Corruption System (Sistema Nacional Anticorrupción, SNA), civil society organizations like Mexicans Against Corruption and Impunity (Mexicanos Contra La Corrupción y La Impunidad, MCCI) and Transparencia Mexicana, and citizen initiatives, including the “3for3 Law,” which calls upon elected representatives to disclose personal assets, conflicts of interest and taxes.

Nonetheless, the aforementioned anti-corruption stamina is arguably waning in the face of staunchly institutionalized corruption. The new anti-corruption system, SNA, has been hard-pressed to accomplish much against active government resistance, including, federal-level refusal to cooperate with corruption investigations, state-level inaction on constitutionally mandated deadlines, and multi-level withholding of information. Regardless of the government’s role in creating the SNA, critics argue that the initiative has been largely abandoned. Juan Pardinas, President of the Mexico Institute for Competitiveness, dubbed this abrupt turnabout a Mexican government placebo scheme, intended to quell public outrage without any substantial compliance (New York Times).

Although anti-corruption progress has been slow, there is hope for the future. With Mexico’s upcoming presidential elections in 2018, it is fair to assume that anti-corruption will be at the forefront of campaign platforms, seeking to allay public indignation and redeem government approval ratings. Likewise, this timely window of opportunity will offer the public a chance to demand pivotal action on anti-corruption reform and impress upon the future administration the strength of public will in Mexico.

For a recent, in-depth summary of anti-corruption efforts in Mexico, Justice in Mexico recommends reading the aforementioned New York Times article. See below.

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/12/02/world/americas/mexico-corruption-commission.html

Sources

Ahmed, Azam. “Anti-Corruption Drive, Commissioners Say.” The New York Times. December 2, 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/12/02/world/americas/mexico-corruption-commission.html

Amparo Casar, M. “México: Anatomía de la corrupción. Instituto Mexicano para la competitividad A.C., Centro de Investigación y Docencia Económicas. May 2015. http://imco.org.mx/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/2015_Libro_completo_Anatomia_corrupcion.pdf

People and Corruption: Latin America and the Caribbean. Transparency International. October 2017. https://www.transparency.org/whatwedo/publication/global_corruption_barometer_people_and_corruption_latin_america_and_the_car

Vice, M. and Chwe, H. “Mexicans are downbeat about their country’s direction. Pew Research Center. September 2017. http://www.pewglobal.org/2017/09/14/mexicans-are-downbeat-about-their-countrys-direction/