09/30/20 (written by lcalderon) – Justice in Mexico, a research-based program at the University of San Diego, released a working paper by Juan García Cruz entitled, “Antes y Después: Análisis comparativo de casos de sistema de justicia penal tradicional y del sistema acusatorio”. The study is a result of the #compara project that compiles a series of indicators curated by Justice in Mexico as part of the “Justicia en Marcha” initiative to measure the implementation and consolidation of the Accusatorial Criminal Justice System (Sistema de Justicia Penal Acusatorio, SJPA). Specifically, the paper compares and analyzes some of the main procedural differences between the Traditional Inquisitorial Criminal Justice System (Sistema de Justicia Penal Tradicional Inquisitorio) and the SJPA. To make this comparison possible, the author draws on three specific cases that share important similarities and were processed under the two different criminal justice systems. The results suggest that there is an apparent consolidation of the SJPA —at least from an analytical perspective— that allows several benefits that were not possible under the traditional system.

In order to select the cases to compare, García Cruz developed a methodology that consisted in finding cases from both criminal justice systems that were as similar as possible and allowed to highlight some of the key elements of each process. The main criteria evaluated were:

- Type of crime

- Number of defendants

- Conclusion of the criminal proceeding (oral trial or ordinary process)

After describing the selection process, García Cruz analyzes the compiled information. For the traditional system, the author needed to conduct an exhaustive revision of all court records or each case. For the SJPA, the author conducted an extensive record analysis as well as reviewing court recordings for each case. Based on this analysis, García Cruz identified 7 main indicators that allowed comparing the different procedures for each system:

- Evidence

- System principles

- Process duration

- Victim treatment and the role of the complaining party

- Volume (size of the court records)

- New figures

- Judges’ impartiality

The working paper examines the procedural differences in three crime types: kidnapping and organized crime; fuel theft; and crimes against public health.

Main Findings

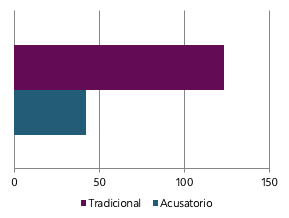

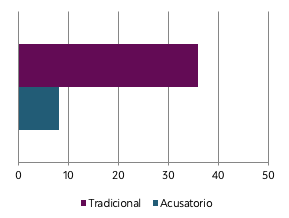

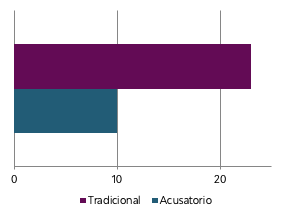

Evidence

- Most of the evidence presented under the SJPA consisted of testimonies. Documents and court records are not considered in the SJPA unless they are mentioned and properly incorporated by the appropriate party during direct examination.

- Under the traditional system, most of the evidence consisted of written documents and statements. In addition, the evidence value of such statements was pre-determined under the Criminal Procedures Code (Código de Procedimientos Penales).

- Presenting testimonies under the SJPA allowed for the participating parties to conduct direct and cross-examinations to the witness, a benefit that was not possible under the traditional system.

- The total amount of evidence presented under the SJPA was significantly lower than in the traditional system. In addition, evidence under the traditional system was diverse and consisted of statements, testimonies, testimony complements and additions, court records and official documents, and ratifications, while under the SJPA most of the evidence consisted of testimonies.

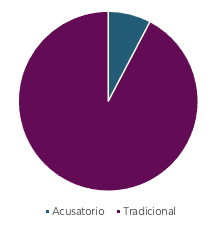

Figura 1: Pruebas (Comparativo I)

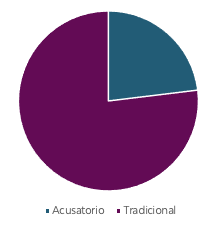

Figura 2: Pruebas (Comparativo II)

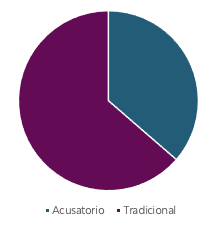

Figura 3: Pruebas (Comparativo III)

System principles

- Cases analyzed under the SJPA emphasize the presence of main system principles such as: contradiction and immediacy.

- While procedures under the traditional system were considered public, institutions often denied the presence of external people. Under the SJPA, the public is welcome to attend,including the defendant’s family and law students.

- In cases under the SJPA it was also possible to identify the principles of consolidation and continuity.

Process duration

- In the three comparisons, cases under the SJPA required less time than cases under the traditional system.

- In terms of complementary investigations, all SJPA procedures were concluded before the legal six-months limit. This limit was not met on cases under the traditional system, resulting in significant delays in the process.

Victim treatment and the role of the complaining party

- In the kidnapping and organized crime case under the SJPA, all victims intervened through their legal advisors throughout the process and had their image protected (blurred) during the oral trial, where they provided testimony from a different courtroom. Under the traditional system, however, victims were required to face their aggressors, allowing re-victimization.

- The role of the legal advisor was key in cases under the SJPA, where they were able to be in all the proceedings, offer evidence, and examine witnesses, among other benefits that were not possible under the traditional system.

Volume (size of the court records)

- The orality factor of the SJPA allowed for smaller court records, while the traditional system required all in writing, making up large volumes of court records.

- In addition, cases under the SJPA have their court proceedings recorded on video, rather than paper.

Figura 7: Volumen (Comparativo I)

Figura 8: Volumen (Comparativo II)

Figura 9: Volumen (Comparativo III)

New Figures

- Judges under the SJPA are required to ensure the right to adequate defense, giving them the authority to substitute the defense if they do not meet the standard. Under the traditional system, defendants could be represented by a trustee without requiring the legal certifications to provide an efficient defense.

- In the case of crimes against public health, there was also the use of stipulations of facts under the SJPA. This allows the court to disregard incontrovertible facts and focus the debate to make the process faster.

Judges impartiality

- In cases under the SJPA, judges were not involved in the previous stages of the oral trial, allowing them to resolve the matters based on facts presented during the proceeding. Under the traditional system, the same judge was in charge of preliminary proceedings and sentencing, making it complicated for the judge to stay unbiased and reconsider his rulings.

Final thoughts

Lastly, the author offers a series of final considerations, emphasizing the importance of studying and understanding the different nature of both systems in order to measure the consolidation of the SJPA and assess the benefits presented by the accusatorial system.

About the author:

Juan García Cruz is a Mexican attorney. He graduated from the School of Law at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) where he also completed a graduate diploma on Criminal Law. Mr. García studied

Criminalistics, and got a Masters of Criminal Procedural Law and Oral Trials by the Universidad Analítica Constructivista de Mexico (UNAC). He is a Research Associate at the University of San Diego’s Justice in Mexico

Program. He has collaborated with non-governmental organizations dedicated to human rights training and analysis of the criminal justice system in Mexico. He has also actively collaborated at UNAM’s Human Rights Program. Currently Mr. García is an Auxiliar de Gestión Judicial at the Federal Criminal Justice Center Mexico City. His academic and professional interests include criminal justice, transitional justice and human rights.