09/24/20 (written by mlopez) – Nuevo Léon’s penal system has been facing critique as the protocols and adherence of inmate rights are being questioned by locals and authorities. The prison system in Mexico has long had its issues with overcrowding and gang violence, as well as recent complications with COVID-19. These factors are making the cells inhabitable for Nuevo Léon’s inmates. Families of the detained are now calling for a fair and impartial investigation into these prison environments.

In September 2020, two respected human rights watch group organizations — Human Rights Watch (HRW) and the Ciudadanos en Apoyo a Los Derechos Humanos (CADHAC) — co-authored a letter demanding the investigation into the suspicious deaths of three inmates. HRW’s Jose Miguel Vivanco and CADHAC’s Hermana Consuelo Gonzales addressed the letter to Nuevo Leon’s governor, JRC, “El Bronco.” In it, they ask for clarity on the prisons Apodaca 1 and 2.

In these jails, there are allegations of gang violence and corrupt payoffs, unsafe and unhygienic social distancing and safety guidelines pertaining to COVID-19, and a lack of medicinal support for any COVID-19 cases. The three deaths mentioned in the letter by HRW and CADHAC add to the complaints made by other inmates’ families and have raised suspicion among the public. The first involved Estanislao Aguilera Escamilla, who died of electrocution on July 14, within a day of being detained. The second victim was Modesto Martínez de la Cruz who died of pneumonia on July 24, within three days of being detained. Just two weeks later, Óscar Hugo de León Martínez was also found dead after having allegedly committed suicide. HRW and CADHAC are urging Governor Rodríguez Calderón to take action in these prisons and to protect prisoners’ rights.

Nuevo Léon’s prisons

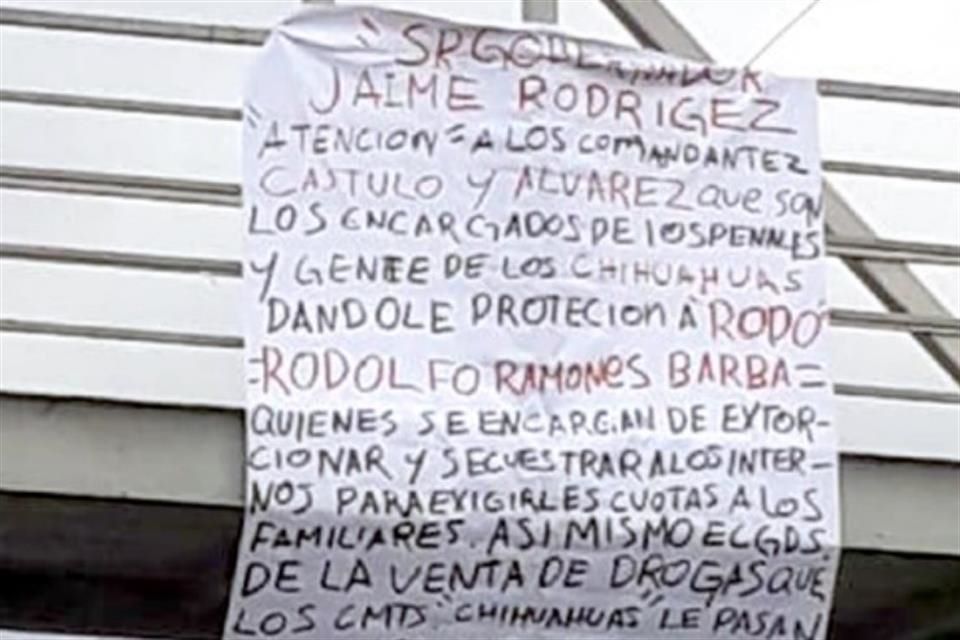

The prisons themselves have been harshly critiqued by authorities and by the families of inmates. El Norte’s Christian Lara reported on the display of mantas (banners) in Monterrey Plaza. This public display was an attempt to bring the conditions of the prisons to the forefront of the issues that Nuevo Léon is facing. These issues include penitentiaries that are overcrowded, influenced by gang activity, and unsanitary. Overcrowded prisons have a low guard to inmate ratio, there is supposed to be 1 guard per 3 inmates, yet realistically there is one guard per every 5.91 prisoners. Due to this imbalance of guards, riots and gang violence persist through the detention centers. Two notorious such riots were those of Topo Chico in 2012 and 2016. While authorities have promoted cutting the lifeline of gangs in detention facilities, there are still allegations of families having to pay off gang leadership in prisons to protect their families that are incarcerated. Carlos Jáuregui, former public security secretary, stated, “the problem is that the majority of Mexican prisons are out of control. They are run by organized crime and the prisoners themselves.”

Shutting down of Topo Chico

The 2016 closure of Topo Chico, in Monterrey, Nuevo León, was in response to how inoperable the facility was and due to all the violence that erupted in this facility. Its closure meant the relocation of 2,000 inmates to Apodaca 1 and Cadereyta with the caveat that they would be under surveillance. Some lawyers saw this move as dangerous as it would be a mezcla — or mix — of gang leadership, which could result in more violence. Many inmates have detailed that certain cartels and gangs controlled various aspects of Topo Chico, signifying the prison officials were out of the loop. Yet, Carlos Martín Sánchez Bocanegra, Director of prison reform group Renace, claimed Topo Chico was primarily shut down because it no longer met national standards, citing a shortage of custodians. Meanwhile, others claim that it was the prison’s infrastructure that posed a threat to the guards, visitors, and inmates.

Topo Chico was the home to the largest penal massacre due to gang violence between Zetas and the Gulf Cartel, two of the most notorious organized crime groups in Mexico. This resulted in 49 dead and the escape of 37 gang leaders. Nevertheless, despite the massacre, the Zetas and the Gulf Cartel were still believed to have had influence within the prison. Governor Rodríguez Calderón responded to these prison riots saying “The self-governance (of prisons) will not return because we made the decision: no more extortion of prisoners, of depriving people’s liberties, to their families that have lost heritage as well as tranquility. Imagining and building are what is best. I imagine that Nuevo Léon will recover its happiness.” [author’s own translation]

COVID-19 as a new factor in prisons

The latest challenge to the livelihoods of prisons is the novel coronavirus. Although Governor Rodríguez Calderón encouraged all of the state’s businesses to implement the proper guidelines to reduce the virus’ spread, prisons have fallen through the crack with reports of minimal social distancing measures in place. In fact, 37% of Mexico’s detention facilities report having overcrowded cells. “Our main aim is to depressurize the prisons in the face of the overpopulation we have,” Maribel Cervantes, the security secretary for Ciudad de Mexico, told EFE. She further highlights that the state’s prisons are designed to house 13,500 inmates but currently contain 31,000 prisoners. With the lack of COVID preventative measures, there is also a lack of proper testing for inmates. Citizens in Monterrey Plaza called for intervention from “El Bronco” by means of the banners they displayed in May of this year. Since then, prisons reportedly have had 100 cases of Covid-19, 79 suspected cases, nine deaths, and three riots linked to the virus since the outbreak of the pandemic according to Mexico’s National Commission for Human Rights (Comisión Nacional de Los Derechos Humanos, CNDH).

There has yet to be a response from “El Bronco” on this specific letter from the HRW and CADHAC. However, Mexico has responded to the inefficient health measures in prisons by asking the judicial branch to release at least 380 prisoners who are serving under five-year sentences or are chronically ill to minimize the crowding in prisons. Penitentiaries are notorious for having substandard living conditions, yet Mexico has been attempting to rebrand the prisons in the country. The 2016 reform of Article 18 in the Mexican Constitution, for example, further defines the mission of detention centers as a resocialization effort to promote work, education, sport, health, and basic human rights. The overcrowding, lack of gang control, and inefficient prevention of disease present serious challenges to upholding this mission.

Sources:

“Nuevo Léon opens its doors to reveal 76 years of history,” Mexico News daily. September 2019.

Carrizales, David. “Topo Chico Cierra Penal Incontrolable,” El Universal. September 9, 2019.

Lara, Christian. “Aparecen mantas; reportan ‘abusos’ en penales,” El Norte. May 24, 2020.