12/02/20 (written by vrice)— Florisel Ríos Delfín, Mayor of Veracruz’s Jamapa municipality, was kidnapped from her home late on November 10, 2020 by ten armed men. The mayor was found dead early the next morning in a rural area of Medellín de Bravo, a neighboring municipality. Police speculate that an organized criminal group was behind the attack. In Mexico, such violence against local mayors, former mayors, mayoral candidates, and alternate mayors has become increasingly frequent. Justice in Mexico’s (JIM) Laura Calderón argues that this violence threatens the democratic process and undermines rule of law.

A Disarmed Police Force and Accusations of Corruption

Ríos is the second female mayor murdered during the term of Cuitláhuac García Jiménez, current governor of Veracruz. Maricela Vallejo, the mayor of Veracruz’s Mixtla de Altamirano municipality, was murdered in April 2019 alongside her husband and driver. The Saturday before her murder, Mayor Ríos attended a meeting with all the other municipal presidents of Veracruz affiliated with the Revolutionary Democratic Party (Partido de la Revolución Democrática, PRD). At the meeting, the mayor expressed feelings of being in danger and asked for help. In her last interview before the murder, she voiced similar sentiments of fearing for her life, which she attributed to the disarmament of local police and a municipal budget that was insufficient to pay for personal security. Veracruz Government Secretary Éric Cisneros Burgos had ordered for Jamapa police to be disarmed shortly before Ríos was killed because the majority of officers had been using firearms that were not registered and approved by the Mexican Secretariat of National Defense (Secretaría de la Defensa Nacional, SEDENA). Therefore, the officers had been using the weapons illegally. In the week before her murder, Ríos met with Secretary Cisneros to request that she and her family receive state protection. Cisneros denied the request.

Since she took office in 2018, Ríos’ term was marred by various scandals. Last July, the Captain of the Jamapa Municipal Police, Miguel de Jesús Castillo, accused the mayor of being involved in the disappearance of citizens. The Captain was later murdered and dismembered by what police suspect to be a criminal organization. Then, in January of this year, the Jamapa municipal palace was occupied for various months by protesters who demanded that dismissed workers be rehired. The occupiers also filed eight complaints with the Veracruz State Attorney General (Fiscalía General del Estado, FGE) against Ríos and other Jamapa government officials for mismanagement. Then, early this November, Ríos’ husband, Fernando Hernández Terán, now ex-president of Jamapa’s National System for Integral Family Development (Sistema Nacional para el Desarrollo Integral de la Familia, DIF), was accused of diverting public funds. After the Veracruz FGE ordered for his arrest, Hernández went into hiding, where he remained at the time of Mayor Ríos’ murder.

Responses

In his daily morning press conference on November 12, President Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO) mourned Mayor Ríos’ death and said that his administration has been attentive to the ongoing investigation. Local Jamapa politicians and leaders of the PRD, the National Action Party (Partido Acción Nacional, PAN), and the Institutional Revolutionary Party (Partido Revolucionario Institucional, PRI) also lamented Ríos’death. Veracruz PAN Senator Indira Rosales requested that Governor García clarify the circumstances of the murder and sanction those responsible. Leaders like Citlali Medellín Careaga (PRI mayor of Tamihua) and Viridiana Bretón Feito (PAN mayor of Ixhuatlán del Café) denounced and demanded justice for Rios’ murder. Via Twitter, Jesús Zambrano Grijalva, National President of the PRD, used the anti-femicide #NiUnaMenos hashtag to condemn Ríos’ murder and criticize Governor García’s administration.

Additionally, Ángel Ávila, the PRD representative in the National Electoral Institute (Instituto Nacional Electoral, INE) took to social media to say that the Governor and Secretary Cisneros should stop threatening the PRD and instead “get to work.” Ávila also denounced Veracruz as a state that “doesn’t have a government.” For his part, the Governor released a video on Twitter sharing that his administration had requested for the FGE to accelerate investigation into Ríos’ death. The Veracruz Secreatariat of Public Security (Secretaría de Seguridad Pública, SSP) shared via Twitter that air and ground surveillance operations had been launched in Jamapa and the surrounding area to investigate and find those culpable for the mayor’s murder. From his unknown location, Ríos’ husband published a Facebook message mourning his wife’s death and attributing unsafe conditions in Mexico to rampant organized crime.

On November 16, Jamapa municipal employees along with dozens of citizens protested in the streets to demand justice for the mayor’s murder. Ríos’ children were also in attendance, including her daughter Yzayana Hernández Ríos, who has since taken over presidency of Jamapa’s DIF since her father’s removal. Yzayana said that she feared for the lives of herself and her siblings and reproached statements by Governor García, which she said blamed the Mayor for her own murder. Ríos’ daughter Yzayana also stated, “My mother was a very hardworking and honest woman, who day to day fought to improve this municipality” and accused Governor García of “re-victimizing” her mother.

The Assassination: An Exception or Endemic?

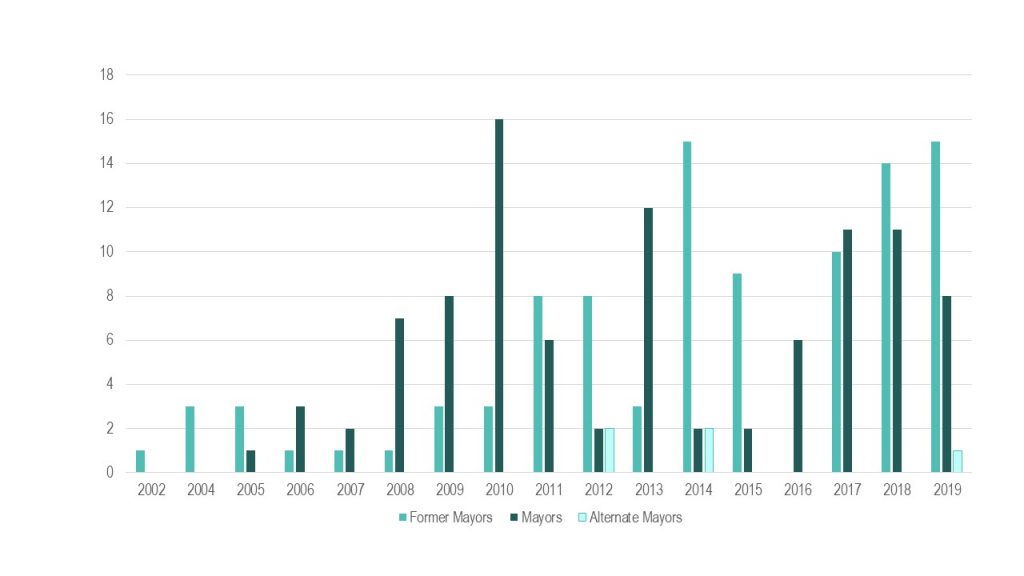

Thus far in 2020, four municipal public servants have been murdered. This violence is part of a larger pattern, exemplified in data from the National Association of Mayors (La Asociación Nacional de Alcaldes, ANAC), which found that 158 Mexican mayors were murdered from 2006-2019. Justice in Mexico’s research has documented the intentional homicide of at least 264 local politicians from 2002-2019, 98 of whom were murdered just from 2015-2019. While JIM’s analysis revealed a 26% decrease in the number of victims from 2018 to 2019, this past year of 2019 was the most violent for ex mayors, who accounted for 15 of the 25 total murders.

Photo: Justice in Mexico

The killing of Mayor Ríos is consistent with other data Justice in Mexico has collected regarding violent conditions in Veracruz and the political affiliation of murdered mayors, former mayors, mayoral candidates, and alternate mayors. While significantly behind the PRI with 89 victims, those affiliated with the PRD—Mayor Ríos’ party—were murdered at the second highest rates of any party, with 40 victims from 2002-2019. Moreover, Justice in Mexico found that during this period, Veracruz reported the fourth highest murder rate of for the aformentioned local politicians. In 2019, Veracruz also recorded the second most murders of mayors, former mayors, mayoral candidates, and alternate mayors (3) nationwide, the highest number of femicides (157) and of officially reported kidnappings (298), and the fourth most cases of extortion (560).

Justice in Mexico’s research has revealed the unique vulnerability of local politicians in Mexico. In 2019, it was revealed that Mexican mayors were 13 times more likely to be assassinated than the general public. The murder rate for mayors was 3.25 per 1,000 mayors, versus 0.24 per every 1,000 citizens amongst the general public. In a working paper by JIM’s Calderón, “An Analysis of Mayoral Assassinations in Mexico, 2000-17”, three potential hypotheses to explain mayoral murders are explored: a mayor’s perceived level of corruptibility (which influences how much organized crime groups view them as a threat), rates of drug production/trafficking in a state (violence is more concentrated in states with of such higher rates), greater vulnerability in more rural territories with less population density. To combat this violence, Calderón emphasizes: the responsibility of the federal government to provide sufficient budgets and adequately enforce federal protections; the fundamentality of strengthening state institutions with transnational justice processes to allow for democratic consolidation; and the necessity of implementing policies and social incentives to dissuade public participation in organized criminal activities as a means of survival.

Violence Against Women in Mexican Politics

The phenomenon of “political violence and political harassment against women,” seen across Latin America and the world, can be characterized by “behaviors that specifically target women as women to leave politics by pressuring them to step down as candidates or resign a particular political office” (Krook and Restrepo Sanín 2015, 127). Such behaviors may include, but are not limited to, acts of physical, symbolic, psychological, economic, and sexual violence—from kidnapping, rape, and murder to the spreading of false rumors, release of private photographs, and refusal of parties to fund female candidates’ campaigns (ibid, 138).

For many years, Mexico’s General Law on Electoral Crimes failed to collect gender disaggregated data on acts of political violence. This meant that specific statistics for violence against female politicians, like Mayor Ríos, or against women trying to exercise their political rights were unavailable. The Mexican government has slowly taken strides to better protect women’s ability to participate in politics, but these have often not lived up to expectations. A 2008 reform aimed to increase female political participation by “requiring parties to earmark 2% of their public funding to activities supporting women’s leadership development” (ibid, 142). When parties’ accounts were reviewed in 2011, it was revealed that these funds had been used for alternative purposes, like “cleaning supplies, stationery, and fumigation services” (ibid). Even in 2013, when the INE introduced a set of guidelines on implementing the earmark, party leaders openly asked auditors how they could avoid adhering to the requirement (ibid). More recently, in October 2020, the INE unanimously endorsed guidelines for political parties to help combat gender-based political violence. Amongst other requirements, these stipulated that, beginning in 2021, no aspiring candidate can be convicted or accused of domestic violence, sexual misconduct, or have defaulted on alimony payments.

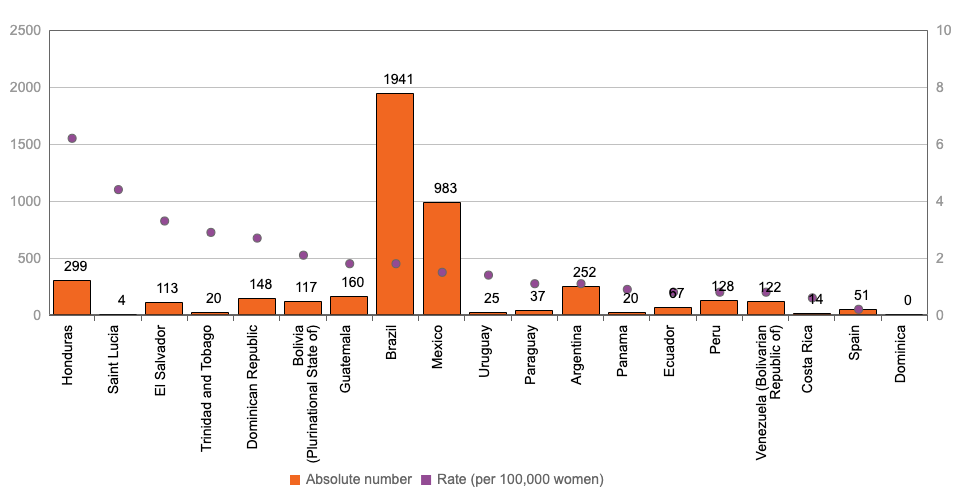

In Mexico, gender-based political violence occurs in a greater context where women’s fundamental rights to life and security are routinely transgressed. In 2019, Mexico recorded the second highest absolute number of femicides in all of Latin America and the Caribbean at 983, a rate of 1.5 per 100,000 women.

This data is reflective of the increasing prevalence of femicide in the country, which from 2015 to 2019 saw a 139% increase, per Mexico’s Secretary General of National Public Security (Secretariado Ejecutivo del Sistema Nacional de Seguridad Pública, SESNSP). These high rates are even more troubling given how in 2019 the impunity rate for femicide in Mexico was 51.4%. This impunity is not just restricted to cases of femicide, but rather is endemic in Mexico, seen by the country’s 89.6% impunity rate for intentional homicides. The Mexican government has played a significant role in allowing rampant violence against women to continue. Of the 3,522 Public Ministry (Ministerio Público, MP) agencies in the country, only 177—less than 5%—are focused on addressing crimes against women. These few agencies are expected to handle an immense caseload, as 482 women report cases of familial violence each day—equivalent to about 20 cases each hour. Moreover, only 3.3% of these agencies focus on sexual crimes, and are expected to manage the more than 40,281 cases of such crimes that were registered from January to September 2020. The lack of resources and government employees to handle cases of violence against women in these few MP agencies contribute to high rates of femicide and impunity for these crimes.

These dangerous conditions for Mexican women have only been exacerbated by the outbreak of COVID-19. El Sol Mexico estimated that two-thirds of women over 15 years of age in the country would be forced to quarantine with a violent partner. Moreover, during the eight months of lockdown thus far, the National Network of Shelters (Red Nacional de Refugios), which aids female victims of violence and their children, has provided services to over 34,716 women. These requests for help represent a 51% increase from the same period during 2019. The Network registered that 9% of male aggressors (about 3,123 individuals) from whom women sought assistance had military or political ties. This data is particularly troubling given the role of male politicians in perpetrating violence against women in politics. In 2004, a female candidate running for municipal president of San José Estancia Grande (in the state of Oaxaca), Guadalupe Ávila Salinas, was shot dead by the sitting municipal president at that time (Krook and Restrepo Sanín 2015, 140). Other female municipal candidates have been kidnapped by their political opponents, in some instances, by opponents in collaboration with the female candidate’s own party and/or spouse (ibid). All of these rampant forms of violence against women in Mexican politics renders near gender parity in Congress more symbolic than actually indicative of equal rights and respect for women. If it is not telling enough that political gender quotas took 15 years to be implemented, female politicians continue to be discriminated against, prevented from presenting proposals, and denied essential campaign funds. Moreover, men continue to serve as the heads of important legislative bodies including the “Executive Board, Political Coordination Board, and 15 out of 16 party caucuses”.

Failing to address attacks against women in politics allows this kind of violence to continuously be construed as the “cost of doing politics” for women (Krook and Restrepo Sanín 2015, 145). Such an understanding normalizes endemic mistreatment of women both inside and outside the political sphere. As a result, violent acts against women in politics threaten the level and quality of democracy in Mexico and question to what degree women have truly been incorporated as full political actors in Mexico (Krook 2017, 74).

Sources

Krook, Mona Lena and Juliana Restrepo Sanín. “Gender and political violence

“Violencia política contra las mujeres en razón de género.” CNDH México. 2018.

“Femicide or feminicide.” Gender Equality Observatory for Latin America and the Caribbean. 2019.

De la Peña, Angélica. “El Covid-19 y la perspectiva de género.” El Sol de México. March 23, 2020.

“Asesinan a Florisel Ríos, alcaldesa de Jamapa, Veracruz.” Animal Político. November 11, 2020.

“La alcaldesa de Jamapa, en Veracruz, es asesinada.” Expansión Política. November 11, 2020.

“Slain mayor had appealed for help before her murder.” Mexico News Daily. November 12, 2020.

Calderón, Laura. “Violencia criminal contra ediles en México.” Animal Político. November 16, 2020.