12/14/20 (written by aahrensviquez) – Mexican federal prosecutors re-issued warrants on December 4, 2020 for the arrest of Puebla’s former governor, Mario Marín Torres; businessman José Kamel Nacif; and Pueblas’s former subsecretary of Public Security, Hugo Adolfo Karam Beltrán, for the unlawful detention and torture of journalist Lydia Cacho in 2005. This highly publicized case has largely been seen as illustrative of the dangers of being a journalist in Mexico and the government’s failure to hold those responsible to account.

The Case of Lydia Cacho

In 2005, Mexican journalist and activist Lydia Cacho published her book The demons of Eden: the power that protects child pornography (Los demonios del Edén, el poder que protege a la pornografía infantil). The book exposed the protection that businessmen Jean Succar Kuri and José Kamel Nacif were receiving from politicians and other businessmen when they were accused of creating a prostitution and child pornography ring. On December 16, 2005, months after the publication of her book, Cacho was arrested in Cacún at the Center for Women’s Comprehensive Assistance (Centro Integral de Atención a la Mujer) headquarters by members of Puebla’s judicial police force on charges of defamation. She was then transferred back to Puebla to face trial.

It was during her transfer, from December 16 to 17, 2005, that Cacho was tortured by members of the police force. According to ARTÍCULO 19, an independent, nonpartisan organization in Mexico and Central America that advocates for the freedom of press, during the ten hours Cacho was detained, the authorities did not give her food or administer her bronchitis medication, nor was she allowed to sleep. Cacho was only allowed to use the bathroom once and place one phone call during this period. She was subjected to psychological and physical torture, sexual abuse, and threats.

Cacho was eventually released from custody on bail. She went to trial on January 17, 2006 and was fully exonerated on the charges of calumny.

On February, 14, 2006, in an explosive exposé, an anonymous source publicized a phone call between Governor Marín and businessman Nacif that took place prior to Cacho’s 2005 detention. In the phone call, Nacif urges Marín to arrest Cacho so that she would be sexually assaulted in prison in retaliation for her calumny against him. The governor reassures him, saying that he will deliver a “f**king knock over the head” (“p*nche coscorrón”) to Cacho because in Puebla “the law is respected” (author’s own translation). On March 13, 2006, Cacho filed charges against Marín and Nacif, as well as other state figures.

15 Years of Impunity

In the 15 years since Cacho was detained and arrested, only two people have been sentenced in relation to the case. Two members of the police force, including former Puebla police commander Juan Sánchez Moreno, were convicted of carrying out the torture. So far, however, there has been no accountability for those who ordered the torture.

The Cacho case eventually made it to the docket of the Mexican Supreme Court (Suprema Corte de Justicia de la Nación, SCJN). The justices launched an investigation of the case and the involvement of Puebla’s then-governor Marín. However, in a surprise ruling on November 29, 2007, the SCJN voted six to four to not go forward in prosecuting the case. The court found that though there were some violations of Cacho’s rights, they were not severe and did not merit the involvement of the SCJN. At the time, René Delgado, the former editor of the newspaper Reforma, called the 2007 vote a “monumental homage to impunity and cynicism” (author’s own translation).

Seeking justice elsewhere, ARTÍCULO 19 filed a petition on Cacho’s behalf to the Human Rights Committee of the United Nations (UN). The Committee ruled in Cacho’s favor in 2018, formally recognizing human rights abuses against the journalist. They determined that Cacho’s detention was arbitrary, meaning that there was little to no evidence that she had committed a crime at the time of the arrest. The Commitee also found that the arrest and torture had been retaliatory in nature. Additionally, they noted that the sexual nature of Cacho’s torture indicated that she had been discriminated against because of her gender, a protected characteristic. Finally, the Committee found that the state had not fulfilled its obligation to investigate this case and hold those responsible accountable.

Two months after ARTÍCULO 19 presented their petition to the UN, Mexican federal prosecutors brought the charges against the police commanders that carried out the torture ordered by their superiors. In 2016 Succar, who Cacho exposed in her 2005, was indeed convicted of child pornography and child sexual abuse in Cancún and was convicted to 112 years of prison.

Arrest Warrants Issued for Marín, Nacif, and Karam

Finally, in April of 2019, arrest warrants were issued for Marín, Nacif, and Karam. However, they were cancelled in November 2020 by the Third Circuit Court in Cacún through a writ of amparo. Judge María Elena Suárez Préstamo of the First Unitary Court (Primer Tribunal Unitario) reissued the warrant on December 4, 2020 for their arrest after reviewing the case. Marín, Nacif, and Karam are currently fugitives.

Mexican Attorney General Alejandro Gertz Manero reported in July that Nacif was traced to Lebanon and disclosed that they were in communication with the Lebanese government to process his extradition. Cacho sharply criticized Gertz in an interview with W Radio Mexico, claiming that she had located Nacif through her coordination with Europol and Interpol and Gertz had risked her case by making that information and strategy public. She also rebuked him for mishandling her case. She posited that through her work, she and her team also located Marín and Karam, but neither of them have been detained either. Cacho is suspicious that Gertz may have some vested interest in not seeing her case through.

2020 Continues the Trend of Violence Toward Journalists in Mexico

In an article in El País, ARTÍCULO 19 described the Cacho case as a “fight against impunity in one of the most violent countries in the world to practice journalism.” Indeed, violence against journalists in Mexico have been widely publicized and well-documented over many years. Justice in Mexico consistently includes a section addressing violence against journalists in its yearly Organized Crime and Violence in Mexico Special Report.

According to the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), from 1992 to 2020 there were 53 confirmed cases of journalists killed, 67 unconfirmed cases, and four cases of media-support workers were killed in Mexico (“Explore all CPJ data”). The CPJ identifies both homicides cases with motives that have been confirmed to have been related to the journalist’s profession, as well as cases with unconfirmed motives. In fact, this year, the CPJ identifies Mexico as the country with the most homicide cases with five confirmed motives in 2020, followed by Iraq and the Philippines each with three confirmed journalist murders. In 2020, the following journalists were murdered in Mexico:

- María Elena Ferral Hernández of El Diario de Xalapa and El Quinto Poder was murdered on March 30, 2020;

- Jorge Miguel Armenta Ávalos of Última Palabra and Medios Obson was murdered on May 16, 2020;

- Pablo Morragares Parraguirre from PM Noticias was murdered on August 2, 2020;

- Julio Valdivia of El Mundo was murdered on September 9, 2020; and

- Israel Vázquez of El Salmantino was murdered on November 9, 2020.

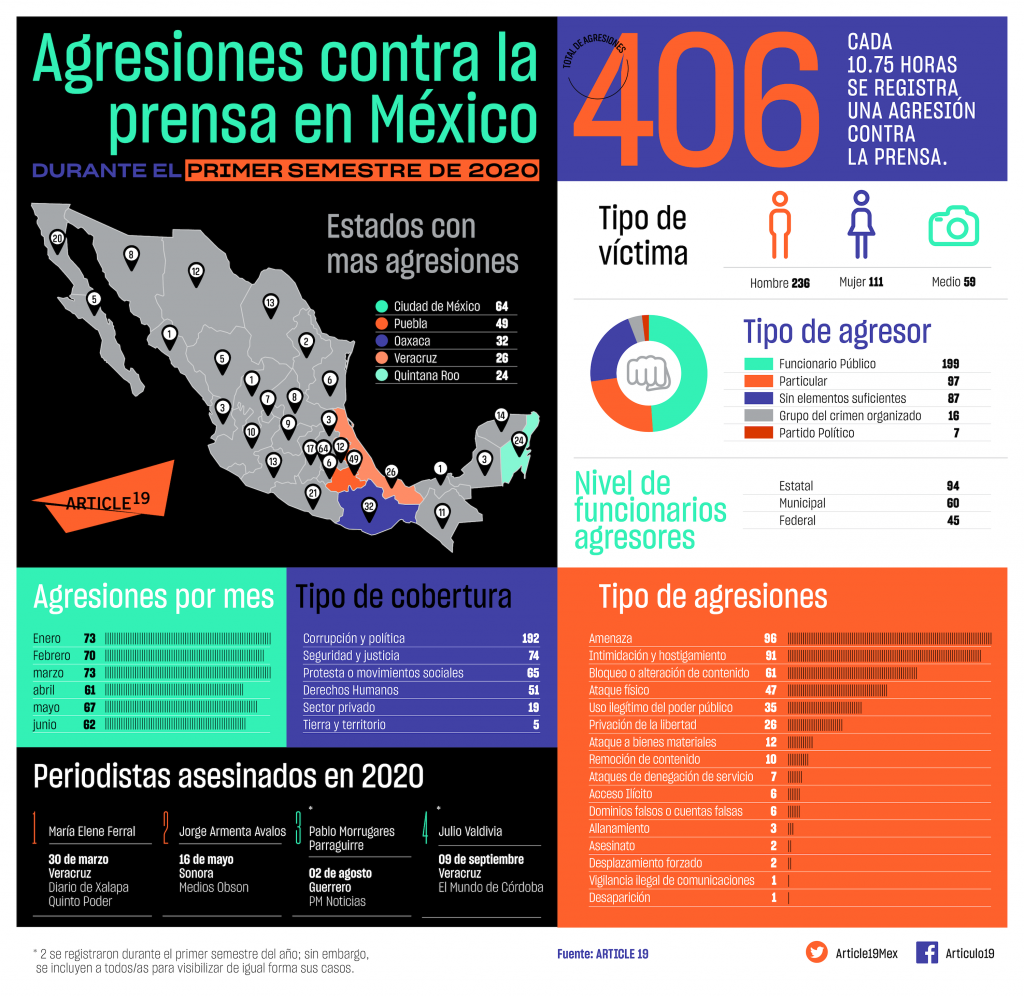

The aforementioned ARTÍCULO 19 has not released their most updated data on violence against journalists in 2020. However, the organization released their tallies for the first six months of 2020 (from January to June 2020). The findings are alarming. The report documented 406 instances of violence or aggression against journalists including cases of threats, harassment, assault, murder, and disappearance, among others. This is up 45% from the 280 cases they identified during the same period in 2019.

In an effort to address the violence against journalists, the Mexican government created the Mechanism for the Protection of Defenders of Human Rights and Journalists (Mecanismo de Protección a Personas Defensoras de Derechos Humanos y Periodistas). Its objective is to provide protection for journalists that were threatened, including temporary relocations, armored vehicles, and security escorts. According to the Mexican National Commission for Human Rights (Comisión Nacional de los Derechos Humanos) report, there is a 90% impunity rate for crimes committed against journalists. Not only does the government often fail to protect journalists and bring their perpetrators to justice, public officials are often the perpetrators of said violence against journalists. ARTÍCULO 19 identifies public officials as the assailants of 199 cases out of the 406 cases of aggression against journalists that were identified in the first six months of 2020.

The Cacho case is a poignant, public exemplification of the issues facing Mexican journalists. She was victim to institutionalized torture at the hands of public officials in retaliation for holding power to account. Even with evidence against her assailants so widely publicized, she was unable to obtain justice from the government. Even now that her case was reopened, the arrest warrants have not been carried out, with very little hope that they ever will be. Moreover, she maintains that the justice system has continued to mishandle her case. Her public ire after 15 years is the same frustration that is inherent to being a journalist in Mexico.

Sources

“Gober precioso.” Youtube.com. February 13, 2007.

Relea, Francesc. “La impunidad ya tiene carta blanca en México.” El País. December 5, 2007.

Castro, Aída. “Cronología: Caso Lydia Cacho.” El Universal. June 2, 2008.

“Juez ratifica condena a Jean Succar Kuri por abuso de menores.” Regeneración. August 10, 2016.

“ONU reconoce violaciones a los derechos de la periodista Lydia Cacho.” ARTÍCULO 19. August 2, 2018.

Vivanco, José Miguel. “El luto del periodismo en México.” Human Rights Watch. June 11, 2020.

ARTÍCULO 19. “15 años de impunidad en el ‘caso Lydia Cacho’.” El País. November 16, 2020.