12/5/16 – (Written by Rita Kuckertz) In October of this year, the International Journal of Conflict and Violence featured an article by Justice in Mexico Program Coordinator Octavio Rodríguez that explores the complexities of Mexico’s recent upsurge in violence. The article, entitled “Violent Mexico: Participatory and Multipolar Violence Associated with Organised Crime,” examines the six-year period from 2007 to 2012 during which Mexico experienced a significant increase in extreme violence. As Rodríguez notes, more than 120,000 deaths were recorded and intentional homicides increased by over 200 percent during this timeframe.

Mexico as an Extremely Violent Society

In order to characterize this wave of violence in all of its complexities, Rodríguez employs Christian Gerlach’s “extremely violent societies” (EVS) methodology —a descriptive framework that may be used to understand violence where multiple groups, including the state, participate in and become victims of said violence. As Rodríguez explains, in an EVS, various social groups participate in the violence due to a wide array of motives or interests. Additionally, a society that is characterized as an EVS often experiences high levels of state imposed violence and organized crime.

Rodríguez first contextualizes Mexico’s current violence by presenting a brief overview of past violence that has occurred throughout Mexico’s recent history. For instance, he describes armed conflicts such as the Mexican Revolution that characterized the first half of the twentieth century as well as state-generated violence (SGV) of oppositional social movements in the latter half. However, as Rodríguez explains, following a series of economic crises in the 1980s and 1990s, the nature of violence began to change. Robbery and theft increased, and by the mid-1990s violent crimes such as rape and assault also began to increase.

During this time, new organized crime groups (OCGs) were also coalescing following state-run counter narcotic measures that led to the dismantling of the once hegemonic Guadalajara cartel. As a result, many of these restructured organizations began to compete amongst each other for control of certain territories and drug routes. In response to this violence, President Felipe Calderón (2006-2012) intensified militarized efforts to dismantle OCG leadership structures. This strategy, however, seemed to only exacerbate the problem of OCG violence by breaking existing OCGs into smaller, unpredictable, and more violent organizations.

Rodríguez argues the resulting violence occurring from 2007 to 2012 is uncharacteristic of past violence in Mexico. While past upheaval may be traced to ideological, religious, or ethnic conflicts with identifiable actors, the violence that characterized the period from 2007 to 2012 was “participatory and multipolar”; that is, it was perpetrated by many different groups for many different reasons against many different people. Thus, traditional terms or concepts used to characterize incidents of mass violence are not applicable here. For instance, the term “war” is not an accurate characterization in this case, as it implies that all violence is state generated and that its victims are combatants. However, as Rodríguez points out, there are numerous other actors that engage in this violence, including OCGs and even the citizenry, who indirectly perpetuate OC practices or directly participate in them.

Rodríguez argues that the EVS framework is useful in making sense of Mexico’s multipolar violence, as an EVS is marked by various actors, including the state, that engage in violence for a variety of reasons. For instance, while a large portion of Mexico’s recent violence is believed to be related to OC activity, it is estimated that there has also been a substantial increase in non-OC related intentional homicides.

This methodology is also helpful in explaining the wide range of victims involved in Mexico’s recent violence. In an EVS, the majority of the violence that occurs is directed toward several groups of people, rather than just one. Similarly, Rodríguez observes that while violence in Mexico is often directed against OC members, it has also increasingly targeted public officials, journalists, media workers, police, and members of the armed forces.

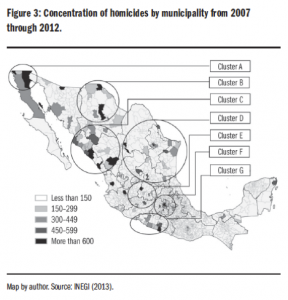

Furthermore, Rodríguez observes that the phenomenon is dispersed geographically throughout Mexico. He identifies seven geographic regions, or “clusters”, that feature similar patterns of violence using data compiled by the National Institute of Statistics and Geography (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía, INEGI). Rodríguez offers a separate explanation for the violence occurring in each cluster, pointing to conflicts between regional cartels and state-led security operations intended to reduce OC. While the violence in these regions is often associated with OCG fracturing and state intervention, Rodríguez maintains that the causes of violence in each cluster are independent of one another—a phenomenon that is characteristic of an EVS.

Rodríguez concludes that there is no existing narrative that properly characterizes the violence that has occurred and continues to occur in Mexico. The author’s final recommendation is to avoid attempts to define the problem as a whole and instead focus on understanding the various forms of violence that are occurring simultaneously throughout Mexico. He emphasizes that there is no “one size fits all” solution to this widespread problem, and as a result, the state and civil society must address each component of this problem individually when considering possible actions. Rodríguez concludes that Mexico must “[consider] the different actors, the different “violences” and their motifs independently, but comprehensively.”

Sources: