03/10/20 (written by kheinle) — Mexico just recorded its most dangerous year on record for women, according to the Secretary General of National Public Security (Secretariado Ejecutivo del Sistema Nacional de Seguridad Pública, SESNSP). Targeted violence against women, also known as “femicides,” has long been an issue with which Mexico has grappled. With the numbers on the rise, critics are turning their ire towards the López Obrador administration to seek answers, action, and accountability.

What the Data Shows

According to the SESNSP, more women were victims of homicide in 2019 than ever before. The number of women who were victims of illicit crimes was also 2.5% higher than in 2018. This included physical injury or assault, extortion, intentional homicide, corruption of minors, femicide, kidnapping, human trafficking, and trafficking of minors. The number of female victims of such crimes reported each year rose from 62,567 in 2015 to 72,747 in 2018, only to be surpassed in 2019 with 74,632 victims. This represents a 137% increase over the past five years in such crimes against women. Women are also murdered at an astounding rate in Mexico, with ten women killed each day, writes The Associated Press. In 2019, more than 1,000 of Mexico’s 35,588 homicides were categorized as femicides. The country’s notorious levels of impunity compound the issue.

The data release comes amidst backlash in Mexico from citizens and human rights advocates demanding the government step up its efforts to protect women. Three specific cases of gender-based violence have thus far caught the country’s attention in 2020, prompting significant protests, a march, and a nationwide strike.

High Profile Cases

The first case surrounds the murder of 26-year-old Isabel Cabanillas, a young artist and feminist who was shot dead in Ciudad Juárez while riding her bicycle on January 18, 2020. Protestors took to the streets of Juárez a week later demanding the government protect women and hold those responsible accountable for their crimes.

Then, on February 9, 25-year-old Ingrid Escamilla’s body was found in Mexico City, stabbed to death and partially skinned by her partner. Photographs of Escamilla’s body were later leaked by the media, prompting even more protests and demonstrations. Activists demanded that the media stop “re-victimizing” the victim and making a public display of the violence. Instead, activists buried the images by flooding the internet with non-violent pictures of nature and artwork linked with Escamilla’s name.

Less than a week later, Mexican authorities discovered the mutilated, naked body of 7-year-old Fátima Cecilia Aldrighett Antón in a plastic bag four days after she went missing. Fátima disappeared on February 11 after videos showed her being picked up from school in Mexico City by a stranger. The mayor of Mexico City, Claudia Sheinbaum, spoke out, calling the child’s murder an “outrageous, aberrant, painful” crime that would “not go unpunished.” Sheinbaum is the first elected female mayor of Mexico City, who campaigned on eliminating violence against women. In July 2019, she vowed “to avoid and eliminate violence against women… It’s not fighting it,” she said. “The objective is ultimately to eradicate violence. That should be the goal.”

Protests Erupt

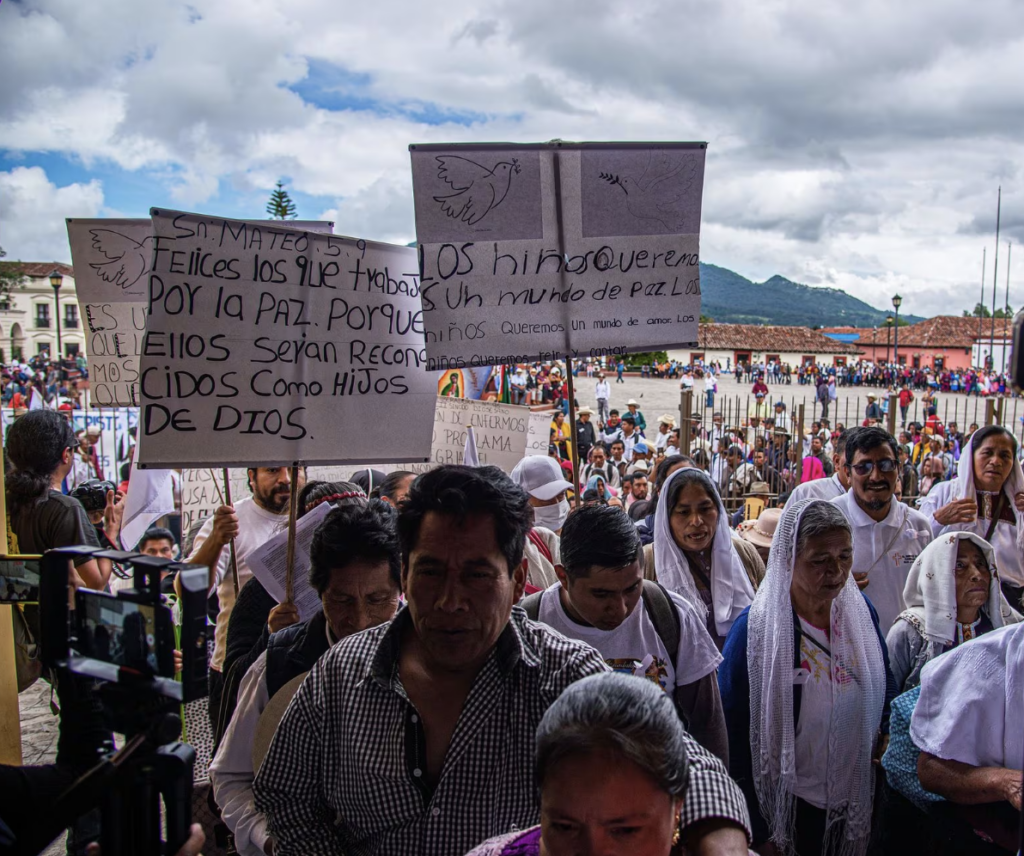

The string of femicides culminating in Fátima’s murder launched a wave of protests throughout Mexico. Activists are demanding an end to gender-based violence and brutality against women, calling for the government to act.

President Andrés López Obrador has specifically come under fire for what protestors say has been his insufficient response to the crisis. The president pushed back, “saying that the issue of femicides have been ‘manipulated’ by those critical of his administration,” writes BBC News. A few of the protests have turned violent with activists throwing “flaming projectiles” at a statue of Christopher Columbus, defacing other statues, smashing cars and setting fires, and spray painting “Femicide state” on the exterior of the National Palace, among other acts.

President López Obrador’s calls for protestors to pacify the demonstrations only further angered participants, writes The Washington Post. Critics argue the president has been dismissive of both the femicides and protests that have ensued; the president counters that demonstrations are just serving as a distraction. Still, the president eventually conceded that “the feminist movement was fighting for a ‘legitimate’ cause,” though he held on to the argument that his political rivals “who want to see his government fail” were instigating the demonstrations.

International Women’s Day March

The protests culminated on International Women’s Day, March 8, when more than 80,000 people marched through Mexico City. It lasted nearly six hours, stretching from the iconic Monumento a la Revolución to the Zócalo city center. At least 38 people in attendance – including several police officers – suffered injuries and needed medical attention. Protestors also hung banners with statements like, “We apologize for the inconveniences, but they are murdering us!” and “I’m marching today so that I don’t die tomorrow.”

The march also featured Vivir Quintana, a 36-year-old musician from Coahuila who sang “Song Without Fear” alongside 40 other women at the Zócalo. Quintana wrote the anthem with the intention to inspire justice and serve as a rallying platform for the women not just in Mexico, but generally throughout Latin America. “At every minute of every week, they steal friends from us, they kill sisters,” sings Quintana. “They destroy their bodies, they disappear them. Don’t forget their names, please, Mister President.”

‘A Day Without Us’

The day after, tens of thousands of women throughout Mexico participated in a strike against gender violence. From classrooms to offices, private to public sector, journalists to street vendors, and beyond, women stayed home during what was dubbed ‘A Day Without Us.’ The strike was meant to show what life would be like without women as more and more become victims of femicide. For the most part, the strike was well supported by places of employment. Mexico City’s Mayor Sheinbum, for example, announced that none of the City government’s 150,000 female employees would be penalized if they did not show up for work on March 9th. According to Mexican business group Concanaco Servytur, had all women participated in the strike the economic impact could have reached $1.37 billion.

As The New York Times summarized, “The unprecedented outpouring of women on Sunday [March 8] and their strike on Monday [March 9] tested the leadership of Mexico’s president.” The events also picked up significant international and social media attention under the hashtags #UnDíaSinNosotras and #ADayWithoutUs. It also paralleled protests and marches throughout Latin America – like the one million-person march in Chile on Sunday – in honor of International Women’s Day.

Read more about cases of femicide in Mexico, violence against women, and underreporting on the crime in these 2019 Justice in Mexico posts here and here.

Sources:

“Allegations of Police Involvement in Rape, Corruption.” Justice in Mexico. August 20, 2019.

Ortiz, Alexis. “2019, el año con más mujeres víctimas en México.” El Universal. February 3, 2020.

“Today in Latin America.” Latin America News Dispatch. February 14, 2020.

“Today in Latin America.” Latin America News Dispatch. February 20, 2020.

“Minuto a Minuto. Marcha por el Día Internacional de la Mujer.” El Universal. March 8, 2020.

Stettin, Cinthya et al. “March 8 de marzo en CdMx: minuto a minuto.” Milenio. March 8, 2020.

“Un día sin mujeres: así luce México sin ellas el 9 de marzo.” Milenio. March 9, 2020.