11/20/19-Justice in Mexico, a research-based program at the University of San Diego, released a working paper entitled, “Violence within: Understanding the Use of Violent Practices Among Mexican Drug Traffickers” by Dr. Karina García. This paper provides first-hand data regarding the perpetrators’ perspectives about their engagement in practices of drug trafficking-related violence in Mexico such as murder, kidnapping, and torture. Drawing on the life stories of thirty-three former participants in the Mexican drug trade—often self-described as “narcos”— collected in the North of Mexico between October 2014 and January 2015, this paper shows how violent practices serve different purposes, which indicates the need for different strategies to tackle them.

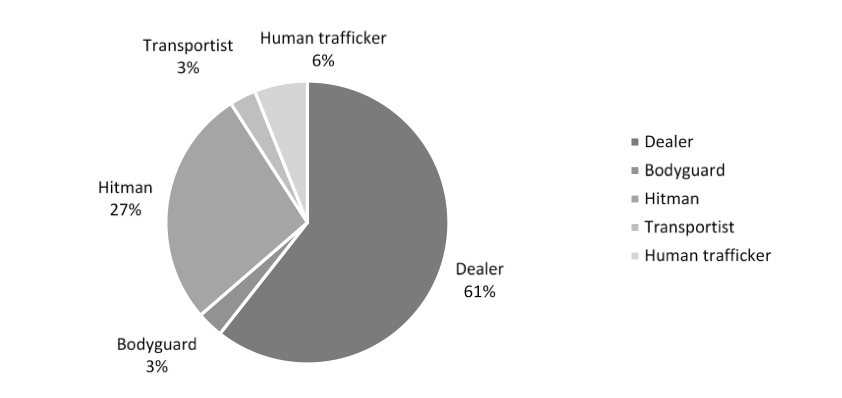

According to the author, there are four dimensions of drug trafficking-related violence identified in participants’ narratives: 1) as a business activity, 2) as a means of industry regulation, 3) as a source of excitement, adrenaline, and empowerment, and 4) as a ritual in the cult of the holy death [la santa muerte]. Practices of violence are normalized by participants in the Mexican drug trade as if it were any other business activity. The logistics of violence in the Mexican drug trade include the casualization of work: workers at the bottom of the hierarchy are conceived as disposable, usually street drug dealers; a clear specialization and division of labour: not all participants in the drug trade—often described as “narcos”—engage in the same type of violence, some focus on torturing people, others on murder, and others transportation and/or disappearance of their bodies.

“Narcos” understand corporal punishments, mutilation and even death, as a way of establishing the ground rules for working within the drug trade. It is taken for granted that, given the illegal nature of the industry, violence is the only way in which drug traffickers can communicate and enforce norms and agreements among themselves, both within their own networks and in relation to their enemies. Murdering and torturing people are practices linked to releasing adrenaline, and even positive emotions such as happiness. Participants suggest that, in the context of poverty, performing acts of violence was the only way they had to feel powerful. Having control over other people’s lives gave them a sense of power that they could not obtain in any other way.

Some participated in violence not only as a necessary business activity, but as a hobby. Former Zetas pointed out that most members are invited to be part of the cult of the holy death [la santa muerte] and some of them are forced to worship her. This cult requires blood, torture and human sacrifices in exchange for protection. Participants explained that they joined this cult in order to have a dignified death rather than living a good life. Drug trafficking-related violence is likely to continue or increase as long as vulnerable groups prone to joining drug cartels remain neglected. In the context of the new administration of López-Obrador, and the creation of the controversial National Guard, this paper’s findings suggest that whereas this new security force may be necessary in some areas of the country, it cannot be the only strategy to minimise drug trafficking-related violence in the long run.

In order to address the first two dimensions of violence, decision makers should consider the legalization of drugs as a way to minimize both violence in Mexico and the quantity of drugs smuggled into the United State. Crucially, legalization should be understood as part of a wider strategy to tackle violence in Mexico. Considering that Mexico is one of the biggest producers of cannabis and opium, it is suggested to fully legalize the production, distribution, and consumption of these drugs in order to reduce the revenue potential of violent, illicit enterprises. The Mexican government should invest more on research and social programs targeted at the poorest and most dangerous neighborhoods in the North of Mexico. Tackling everyday insecurities that children and young men have to cope with is of paramount importance to prevent increased labour pools for drug cartels.

About the Author:

Dr. Karina García is an Assistant Teacher at the School of Sociology, Politics and International Relations (SPAIS) and the department of Hispanic, Portuguese and Latin American Studies (HIPLA) at the University of Bristol. Her research interests include drug policy, drug violence, qualitative research methods, toxic masculinities, and gang violence in Latin America.