02/11/19- Fentanyl overdoses in the United States have risen tenfold in just four years and are now related to 60% of total opioid deaths. According to a working paper by Romain LeCour Grandmaison, Nathaniel Morris and Benjamin T. Smith, the dramatic increase of fentanyl use in the United State is generating a parallel and rapid collapse in the price offered for raw opium in rural Mexico. In the working paper titled “The U.S. Fentanyl Boom and the Mexican Opium Crisis: Finding Opportunities Amidst Violence?” the authors utilize the case studies of two villages in Nayarit and Guerrero, Mexico, respectively, to analyze the socio-political effects of U.S. fentanyl use on the opium and heroin economy in Mexico. The findings of this study have important implications for public security in Mexico, as well as major ramifications for international counter-drug efforts.

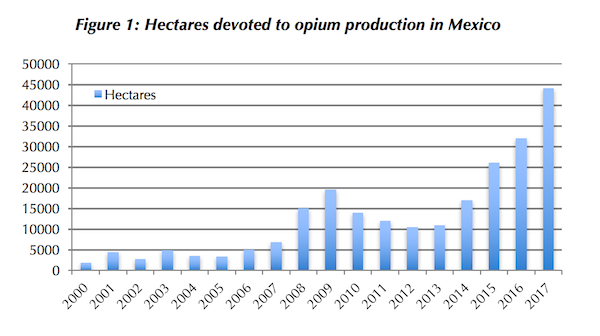

The authors provide historical context to illustrate the trends in the Mexican opium markets. There were various increases and declines in the production of the drug within Mexico before the 1990s. A notable change to opium production came with the introduction of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in 1994, which gradually increased price competition until 2008, thereby negatively affecting Mexican rural communities. As a result, many farmers turned to the cultivation of narcotics. According to United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), the number of hectares of opium poppies in Mexico increased from 1,900 hectares in 2000 to 44,100 hectares in 2017.

The authors illustrate the effects of the shift from heroin to fentanyl through two case studies: Village A, located in Nayarit, and Village B, located in Guerrero. Both villages are poorer than the national average with 61.6% of the population of Village A and 33% of the population of Village B living in extreme poverty. Additionally, both villages are located in states that face high levels of violence.

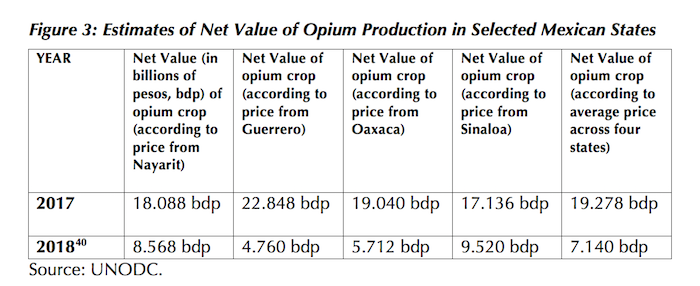

The people of Village A have traditionally depended on agriculture for their livelihoods. Beginning the in mid-1980s, the inhabitants began depending on the cultivation of opium poppies and, to a lesser extent, marijuana to supplement their income with very little knowledge of the laws prohibiting these narcotics. However, with the fentanyl crisis, the last year has seen a more than 50% decline in the price of opium in Village A from 18,000 – 20,000 pesos ($950 – $1,050 dollars) per kilo in early 2017 to 8,000 pesos ($420 dollars) per kilo by mid-2018. As a result, some villagers have emigrated while other have become wage-laborers for drug trafficking organizations (DTOs) that they previously had little contact with.

According to the authors, 95% of males in Village B are involved in poppy production. While most people are involved in cultivation, a substantial number is also involved in the processing of opium paste into heroin. Local drug bosses sell the pure heroin to bigger organizations that are capable of selling and transporting the drug. Before the fentanyl crisis, a local farmer could make around 80,000 pesos ($4,230 dollars) a year through poppy cultivation. However, between October 2017 and the summer of 2018, prices dropped to 6,000 pesos ($315 dollars) a kilo. As with the case of Village A, locals are concerned that should the decline in prices continue, they would be forced to leave their village. The problems confronting the inhabitants of Village A and B signal larger trends, such as the value of opium to rural communities in Mexico and the radical decrease of value of opium over the past year.

The authors offer that the current opium crisis may provide an opportunity to shift from their dependency on illicit crops and away from drug trafficking. The high risk involved in the production of narcotics that was previously outweighed by large returns may no longer be worth it as a result of price declines. In their paper, the authors examine two alternatives widely touted by politicians as solutions to poverty and violence: drug legalization, which could convert the cultivation of opium into morphine production for Mexican hospitals, and crop substitution, or the replacement of the cultivation of illicit crops for food cultivation. The authors find neither of these solutions are “silver bullets.” Additionally, although there has been a reduction in heroin production, this will not likely lead to lasting peace, as DTOs are liable to move to other illicit activities. Despite these concerns, if legalization and crop substitution are properly implemented and combined with broader security policies, they could integrate rural areas into the country for good.