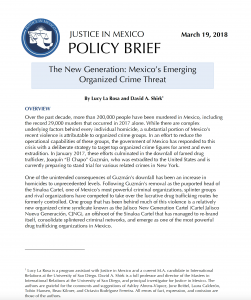

03/19/18 (written by dshirk) – Over the past decade, more than 200,000 people have been murdered in Mexico, including the record 29,000 murders that occurred in 2017 alone. According to a new Justice in Mexico policy brief by Lucy La Rosa and David A. Shirk, the recent increase in violence is one of the unintended consequences of the Mexican government’s strategy to target top organized crime figures for arrest and extradition. In the policy brief, titled “The New Generation: Mexico’s Emerging Organized Crime Threat,” the authors contend that the “kingpin strategy” that led to the downfall of famed drug trafficker Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán has now given rise to a new organized crime syndicate known as the Jalisco New Generation Cartel (Cartel Jalisco Nueva Generación, CJNG).

03/19/18 (written by dshirk) – Over the past decade, more than 200,000 people have been murdered in Mexico, including the record 29,000 murders that occurred in 2017 alone. According to a new Justice in Mexico policy brief by Lucy La Rosa and David A. Shirk, the recent increase in violence is one of the unintended consequences of the Mexican government’s strategy to target top organized crime figures for arrest and extradition. In the policy brief, titled “The New Generation: Mexico’s Emerging Organized Crime Threat,” the authors contend that the “kingpin strategy” that led to the downfall of famed drug trafficker Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán has now given rise to a new organized crime syndicate known as the Jalisco New Generation Cartel (Cartel Jalisco Nueva Generación, CJNG).

The authors provide a detailed history of the CJNG, an offshoot of the Milenio and Sinaloa Cartels. As recounted in the new report, the CJNG has managed to re-brand itself, consolidate splintered criminal networks, and emerge as one of the most powerful drug trafficking organizations in Mexico. Based in Guadalajara, the capital of the state of Jalisco, the CJNG has a widespread and growing presence that authorities say spans two thirds of the country. The CJNG is headed by Ruben “El Mencho” Oseguera, a small time drug trafficker who was convicted in California, deported to Mexico, and emerged as a ruthless and shrewd drug cartel leader.

The authors contend that the CJNG offers a timely case study of how organized crime groups adapt following the disruption of leadership structures, and the limits of the so-called “kingpin” strategy to combat organized crime, which has contributed to the splintering, transformation, and diversification of Mexican organized crime groups and a shift in drug trafficking into new product areas, including heroin, methamphetamines, and other synthetic drugs.

The authors offer three main policy recommendations. First, the authors argue that U.S. State Department and their Mexican partners must continue working earnestly to bolster the capacity of Mexican law enforcement to conduct long-term, wide-reaching criminal investigations and more effective prosecutions targeting not only drug kingpins but all levels of a criminal enterprise, including corrupt politicians and private sector money laundering operations. Second, the authors argue that U.S. authorities must work more carefully when returning convicted criminals back to Mexico, since deported criminal offenders like CJNG leader Oseguera are prime candidates to join the ranks of Mexican organized crime. Third, and finally, the authors contend that further drug policy reforms are urgently needed to properly regulate the production, distribution, and consumption of not only marijuana but also more potent drugs, including cocaine, heroin, and methamphetamine.