06/12/20 (T McGinnis) – 2019 represented the most dangerous year on record for women in Mexico, according to Mexico’s Secretary General of National Public Security (SESNSP). Femicide, a crime that deprives a woman of life as a result of her being female, remains a long-standing and protracted issue with which the Mexican public, policymakers, and legal actors have struggled. With the López Obrador administration declaring an “end to the war” against drug cartels and trafficking, the question remains whether this proclamation will lead to more adequate responses regarding gender violence, responses in which answers and accountability stand at the forefront of the government’s plan of action.

General Overview

What the Available Data Suggests

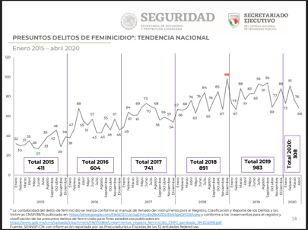

The Secretary General of National Public Security (Secretariado Ejecutivo del Sistema Nacional de Seguridad Pública, SESNSP) reports that between 2015 and 2019, cases of femicide rose from 411 to 983, representing an increase of approximately 139%, as shown by the graphic on the right. This parallels, if not surpasses, Mexico’s broader trend of recorded record-high numbers of murders in 2019. According to Milenio, in January alone of this year, 320 women were murdered (247 victims of intentional homicide and 73 victims of femicide), making an average of 10 cases per day.

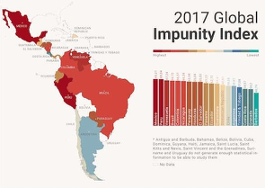

However, the aforementioned figures may be much higher when one accounts for shortcomings and biases in the collection and conceptualization of femicide data. For example, Mexico’s elevated levels of impunity compound this issue further. According to the Center of Strategic & International Studies and the National Institute of Statistics and Geography (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía), “93 percent of crimes were either not reported or not investigated in 2018.” Furthermore, the Congressional Research Service details that the prosecutor general’s office remains underfunded. As specified by the GII-2017 Global Impunity Index (Índice Global de Impunidad), this means that preventive actions with respect to intelligence and the preparation and integration of information into investigative files (carpetas de investigación) remain stifled and ineffective. Thus, the perpetrators of violence are further motivated by the unlikelihood of conviction. With stark gender inequalities and pervasiveness of machismo culture in Mexico, one observes reduced levels of priority for investigations of gender-based murders. When observing the legal context of femicide, penal codes on femicide can vary by state, resulting in “a lack of comparable data and agreed definitions” that make prosecuting cases more difficult. Frequently, for both genders, victims of violence are battered and further discriminated against when trying to access the justice system. For women, the motivation to seek legal recourse or help diminishes significantly, seeing that “77 percent of Mexican women report not feeling safe.” These shortcomings and biases reflected in the available data will become more evident when the legal aspects of femicide are explained in greater detail.

High-Profile Cases in 2020

Mexico has grappled with the issue of gender-based violence and more specifically, femicide for many years, which became a major concern in the early 2000s with the high-profile serial murders of women in Ciudad Juárez. However, recent statistics indicating a nation-wide increase in femicides, as well as three high-profile cases in the first few months of 2020, led to protests and major demonstrations condemning violence against women. The first of the three cases involved Isabel Cabanillas, a 26-year-old artist and feminist who was murdered in Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua on January 18, 2020 while riding her bike. According to NBC, although the dimension of the Mexican federal government tasked with combating violence against women, INMUJERES, classified her death as a femicide, law enforcement authorities described the motive as unclear. This elucidates one of the most apparent issues with the legal category of femicide. In order to classify a crime as femicide, there have to be qualifying characteristics and motives working in tandem with the act of homicide. Some of these characteristics and motives may be clear upon the start of an investigation, while others may not become evident until the case is adjudged. Weeks later, 25-year-old Ingrid Escamilla was murdered by her male partner in northern Mexico City. According to Al Jazeera, her remains were discovered on Sunday, February 9, 2020 with certain organs removed and portions of her body skinned. The next day, the national newspaper Pasala published images of her body, sparking further outrage in the public and an overall repudiation of the way in which the government handles the dissemination of information on femicides. In an El Universal column entitled “Who killed Ingrid Escamilla?”, Alejandro Hope, a political science professor, presents his answer. “A violent and machismo culture killed Ingrid, our indifference killed her, our failure to demand that things change killed her.” The third case involved the murder of 7-year-old Fatima Cecelia Aldrighett Anton, who went missing on February 11, 2020 in Santiago Tulyehualco, Xochimilco. According to El Universal, she was believed to have been abducted at school, where she was left outside and unsupervised as she waited for her mother. Her naked body was discovered on February 15, 2020 in a plastic bag near Los Reyes, Tlahuac.

2020 Protests (International Women’s Day and “A Day Without Us”)

Each of the aforementioned cases resulted in protesters urging president Lopez Obrador to publicly acknowledge his administration’s lack of strategy in protecting the female population, and calls to stop criminalizing women who are victims of femicide. Following International Women’s Day (Mar. 8th), in which 80,000 individuals marched through Mexico City, displaying banners that stated “I’m marching today so that I don’t die tomorrow,” tens of thousands of women furthered the sentiment by participating in a national strike. What was soon deemed “A Day Without Us” strove to demonstrate what life would be like without women as more and more fall victim to femicide every day.

Government Response

In November 2019, Mexican officials had vowed a “zero tolerance” approach to the problem, as they observed the International Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women, in partnership with the United Nations. According to the Council on Foreign Relations, the government has also made a point of emphasizing the existing measures in place, such as gender sensitivity training for armed forces. Additionally, after Escamilla’s murder, president Lopez Obrador joined protesters in denouncing the behavior of the media in leaking the explicit photos and soon praised their efforts in passing a bill that would increase prison sentences for those who commit femicide.

However, although lauded as a socially-progressive leader for perhaps, some of the reasons explained above, The Center for Strategic and International Studies regards president Lopez Obrador’s response to the issue of femicide and more generally gender-violence as “tepid at best.” Critics and activists note that AMLO appears indifferent to the reality of the situation and gendered context, calling himself a “humanist” and not a feminist. In reaction to the March 9th strike, he accused political opponents for the situation of unrest. Furthermore, according to the Council on Foreign Relations, his administration faced backlash when the Attorney General suggested removing femicide from Mexico’s criminal code, even though AMLO later said that he did not support the change. Claiming that the media manipulates the issues surrounding gender-based violence, the CFR reports that president Lopez Obrador also claims that the current crisis remains “tied to his predecessors neoliberal economic policies” and believes that what the country needs is a “moral regeneration.” Moving forward, it remains to be seen whether his public pledges translate into concrete action.

A Deeper Look into the Legal Context of Femicide in Mexico

As the surfacing of the aforementioned data and high-profile cases sheds a greater light on this national epidemic and mobilizes the public to place considerable pressure on Mexican officials, it remains critically important to understand the legal context of femicide in Mexico and how its process of prosecution could affect the data, media, rate of occurrence, etc. Prior to 1992, the term “femicide” had been used by the media and greater society in a colloquial manner to indicate the death of a woman. According to the Organization of American States Inter-American Commission of Women, that same year, Diana Russell and her colleague Jill Radford redefined femicide as “the murder of women, committed by men, for the simple reason of their being women.” In elucidating the gendered motives of men in killing women, which include “attempts to control their lives, their bodies and/or their sexuality, to the point of punishing through death those women that do not accept that submission,” Russell and Radford provided both legal and social contexts to the concept of femicide.

According to El Universal, the concept garnered significant notoriety in Mexico when Marcela Lagarde took the aforementioned notion of femicide advanced by Russell and Radford and further developed it as “feminicidio,” rather than femicidio (which constitutes the literal translation). The OAS Declaration on Femicide reports that “Lagarde’s position was that femicide could be understood as the death of women without specifying the cause, whereas feminicide better encapsulated the gender-based reasons and the social construction behind these deaths, as well as the impunity that surrounds them.” She subsequently used the term feminicide (feminicidio) to analyze a wave of gender-motivated murders in Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, which started around 1993, and continued to substantiate its importance in her professional research.

Before the classification of femicide as a social construct and category of crime, many of these murders were wrongly labeled as “crimes of passion.” According to El Universal, crimes of passion are defined as “a crime committed because of very strong emotional feelings, especially in connection with a sexual relationship.” The same term has also frequently been used to describe violent crimes against LGBT persons. However, once the term “femicide” was coined and the phenomenon was further explained and adopted by the media and public, different facets of the Mexican state began to grasp the gender-based implications of this type of violence against women. Nevertheless, bias and sexism still permeate media reporting of violent crimes against women. For example, “after Ingrid Escamilla was murdered by her partner in early 2020, a newspaper titled the article ‘It was cupid’s fault’ and printed a photograph of her skinned and dismembered body on its cover.” While femicides often occur between romantic partners, it should not constitute the defining aspect of this phenomenon. As previously elucidated by anthropologist Marcela Lagarde, “the explanation of femicide lies in gender dominance: characterized by both the male supremacy and the oppression, discrimination, exploitation and, above all, social exclusion of girls and women.”

According to the Center for Strategic and International Studies, Mexico began counting and including femicide data in 2012. The General Law on Women’s Access to a Life Free of Violence (Ley General de Acceso de las Mujeres a Una Vida Libre de Violencia) proposed by the Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD) in 2007 was one of the legislative measures that predated and influenced the current Federal Penal Code (CPF):

English translation:

Article 325.

The crime of femicide is committed by a person who deprives a woman of life for reasons of gender. It is considered that there are gender reasons when any of the following circumstances occur:

- The victim presents signs of sexual violence of any kind;

- Inflammatory or degrading injuries or mutilations, before or after the deprivation of life or acts of necrophilia, have been inflicted on the victim;

- There are antecedents or data of any type of violence in the family, work or school environment of the perpetrator against the victim;

- There has been a sentimental, emotional or trust relationship between the asset and the victim;

- There are data that establish that there were threats related to the criminal act, harassment or injuries of the perpetrator against the victim;

- The victim has been held incommunicado, whatever the time prior to the deprivation of life;

- The victim’s body is exposed or displayed in a public place.

Anyone who commits the crime of femicide will be sentenced to forty to sixty years in prison and a fine of five hundred to one thousand days.

In addition to the sanctions described in this article, the perpetrator will lose all rights in relation to the victim, including those of a successional nature.

In the event that femicide is not accredited, the homicide rules will apply.

A public servant who maliciously or negligently delays or hinders the prosecution or administration of justice shall be sentenced to three to eight years and a fine of five to fifteen hundred days, and shall be removed and disqualified from three to ten years to perform another public employment, office or commission.

In Nexos magazine, Elizabeth V. Leyva notes that although a fair majority of Mexican federal entities adhere to the federal norm as outlined above, “the truth is that legal classification of femicide is not the same in all laws: each state recognizes this problem with various characteristics with which it can be identified.” As a federal republic with the current criminal law system, states (32 in total) can individually regulate crimes and classify them as they deem appropriate. Thus, it is critically important to analyze and detail the similarities and differences in the classifications of these penal codes in an effort to elucidate whether certain legal provisions impact the number/level of femicides in each respective state.

It is important to understand how the Mexican Federal Penal Code on femicide parallels or differs from legislation at the state level. Firstly, both federal and state penal codes define femicide as a crime that deprives a woman of life for reasons of gender. Because this definition is potentially problematic (“gender” is not the same as a female person), Leyva describes current legislation having an “androcentric” view that disregards the death of a woman occurring as a result of her being female. As a result, critics point out that the legal definition of femicide is flawed by a male-dominant perspective and can lead to an ineffective understanding and enforcement of the law.

The essential qualifying circumstances for femicide are described in the penal codes as “gender reasons,” which can be divided into two categories: 1) The various forms the act of violence can assume and 2) the types of acts that occur before or after the death of the woman. The first category includes the following circumstances:

1.The victim presents signs of sexual violence of any kind

Circumstance one describes that femicide can occur through a nonconsensual sexual act aimed at the subordination and domination of women. Observing trends more generally, according to UN Women, “1 in 3 women over 15 years of age has suffered sexual violence” in Latin America and parts of the Caribbean, which is categorized as an epidemic by the WHO. Additionally, UN Women states that “femicide and sexual violence are closely linked to deficient citizen security, to general impunity and to a macho culture that undervalues women,” all of which are pervasive in the state of Mexico.

5. There are data that establish that there were threats related to the criminal act, harassment or injuries of the perpetrator against the victim

Circumstance five establishes that femicide is not an isolated act that happens without prior signs, but also the result of continuous acts of violence against the victim by the perpetrator. In other words, the perpetrator of a femicide is someone that has sexually or violently abused the victim prior to the murder. A 2019 National Institute of Statistics and Geography (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía) report based on data from Chihuahua details that “43.3% of women have faced assaults from the current or last husband or partner throughout their relationship.” Critics highlight that the Mexican state has been negligent in stopping these chains of attacks before they result in the deaths of women.

2. Inflammatory or degrading injuries or mutilations, before or after the deprivation of life or acts of necrophilia have been inflicted on the victim

Circumstance two discusses the physical characteristics of the violent acts, which include scratches, bruises, cuts, stab wounds, or gunshot wounds, etc. With this reason, one can observe certain ambiguities with respect to operationalizing “inflammatory” or “degrading.” In essence, these injuries and mutilations are expected to be either of the aforementioned designations without having an explicit definition and/or reference point to classify them as such. This could contribute to an ineffective understanding and enforcement of this portion of the law.

The second category of gender reasons encompasses the types of acts that occur before or after the death of the woman.

6. The victim has been held incommunicado, whatever the time prior to the deprivation of life

Circumstance six states that during this crime, women may not be in a position to communicate or request third-party help, leaving them rather defenseless. Leyva notes that “the temporal nature of this sentence is ambiguous because it does not define how long ‘the time prior to the deprivation of life’” actually is. With this, one observes states, like Colima and Sinaloa expanding this notion in a more concise manner, isolating what they are actually attempting to legislate:

When the victim has found herself in a state of defenselessness, this should be understood as the situation of real helplessness or incapacity that makes her defense impossible. Either due to the difficulty of communication to receive help, due to the distance to an inhabited place or because there is some physical or material impediment to request help.

7. The victim’s body is exposed or exhibited in a public place

According to Leyva, though this may appear circumstantial to the crime of femicide, it possesses a powerful significance. In her text Women and the Public Sphere: A Modern Perspective, Joan Landes, a professor of Women’s Studies and History at Pennsylvania State University, postulates that women were denied status as a political subject when conceptions and definitions of political subjectivity, and more generally, politics were shaped in the pre-modern era. As actors in the private sphere, their treatment and struggle for human rights was, and still is, made invisible. With women now occupying positions in the labor market and public sphere, men often confuse female liberation as an intrusion of sorts with respect to previously solidified gender roles. Thus, when men commit femicide and display the body in the public arena, they are sending a psychological message for women to stay home. This aspect of femicide is often made worse when the public and political actors blame the victim for walking home alone or not being home as the patriarchal narrative expects.

Once convicted of committing femicide, punishments vary decidedly between states. In comparing the penal codes, the minimum sentence for femicide is 20 years in prison, while the maximum constitutes 70 years. Additionally, beyond the previously discussed, basic components observed in the entities’ penal codes, certain states present interesting additions and considerations worth noting. For example, in Jalisco, the penal code accounts for a variant of femicide known as “lesbofeminicidio” (the murder of a woman because she loves/loved another woman) and “transfeminicidio” (the murder of because she is a transgender or transsexual woman) by including the circumstance of “when the perpetrator acts for reasons of homophobia.” These variants are not popular in other states’ penal codes due to their lack of exposure in the media. In Puebla, one of the additional circumstances constituting a gender reason is “if the victim is pregnant.” This circumstance acknowledges that the perpetrator of the violence is often the biological father and that the crime of femicide may be committed to avoid the responsibilities of parenthood and alimony.

Many critics argue that the statutes for each state’s criminal code on femicide are not uniform, making it especially difficult for third-party groups to ensure effective, nation-wide implementation. For example, there is still no general agreement on whether the act of femicide is a separate category of crime or an aggravated form of homicide. In March and February 2020, many Mexican media outlets, like La Jornada highlighted the danger in a proposal by the Office of the Federal Attorney General (Fiscalía General de la República) to eliminate the designation of “femicide” as a crime and to treat it as an aggravated form of homicide. This would allow for easier facilitation of investigations and prosecutions, the Office of the Attorney General argued. However, the National Human Rights Commission (CNDH) objected, stating that the elimination of femicide as a category of crime would constitute a “setback” because of “the specificity of the content, implications, and meaning of this crime, (because) it makes invisible the essential component of hatred against women, as well as through it seeks to perpetuate the cultural patterns of subordination, inferiority, and oppression of women.”

With the aforementioned analysis on the legal context of femicide in Mexico and the possible threats to its legal standing, it is important to quantitatively determine whether certain legal provisions are responsible for lowering the rates of femicide in certain states. In acquiring this information, the Mexican government could more effectively tailor its federal policy and response to the crime.

Sources

Morales, Gretel. “What is femicide?” El Universal. 27 Feb. 2020.

Leyva, Elizabeth. “El Mosaico del feminicidio en México.” Nexos. 11 Dec. 2017.

Hope, Alejandro. “¿Quién mató a Ingrid Escamilla?” El Universal. 12 Feb. 2020.

Reza, Abraham. “En enero de 2020, cada día 10 mujeres fueron asesinadas.” Milenio. 26 Feb. 2020.

Ortiz, Alexis. “2019, el año con más mujeres víctimas en México.” El Universal. 3 Feb. 2020.

Medina, Ari. “The growing epidemic of femicide and impunity.” Global Citizen. 5 Nov. 2015.