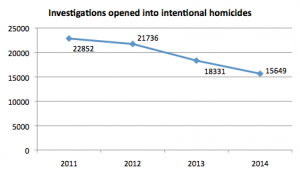

02/02/15 (written by cmolzahn) — As reported in Reforma, the Peña Nieto presidential campaign set a goal in 2012 to reduce intentional homicides in Mexico by 50% in its first year, an ambitious undertaking by any measure. According to data from Mexico’s Secretary General of National Public Security (Secretariado Ejecutivo del Sistema Nacional de Seguridad Pública, SESNSP), there were 15,649 investigations opened into intentional homicides in 2014, representing 13.07 homicides per 100,000 residents. This is down from 18,331 homicides in 2013 (15.48 per 100,000 residents), a 14.6% reduction, and 21,736 in 2012, a 28% reduction. However, as Reforma points out, the reduction in 2013, Peña Nieto’s first year in the presidency, followed a 5% reduction from 2011’s total of 22,852, when violence peaked in Mexico. The question remains how much of the reduction in homicides resulted from changes in public security policy, as opposed to a more natural decline resulting from reduced conflicts within criminal organizations responsible for a share of these homicides, or realignments within these organizations.

While homicides are down in the first two years of the Peña Nieto presidency, situations in Guerrero and Michoacán remain as significant challenges for the administration, and sources of widespread public discontent. In Guerrero, the federal government pronounced that public security operations within 13 municipalities had been controlled by organized crime, prompting its intervention. Tomás Zerón de Lucio, head of the Criminal Investigation Agency of Mexico’s Attorney General’s Office (Procuraduría General de la República, PGR), said that the leadership of municipal police forces had also been handpicked by local criminal organizations to work in their interests. According to Zerón de Lucio, these groups decided which operations would be carried out and when, and that the only distinction between criminals and police was their official designation. As a result, the federal government took over security functions in those municipalities beginning October 20 of last year. These municipalities include Iguala, where 43 teacher trainees were abducted by local police controlled by a local criminal organization and acting on the behest of the mayor and his wife. To date, only one set of remains has been identified as belonging to the 43 disappeared students, but the PGR released a statement this month maintaining its position that the students were murdered and their bodies incinerated, and that it would not open any new lines of investigation into the matter. Nevertheless, Amnesty International has called on Attorney General Jesús Murillo Karam to continue searching for the missing students, given that the extent of the PGR’s intelligence regarding their whereabouts has come from admitted criminals.

Meanwhile, in Michoacán, which has been another focal point for public security efforts given the rise of the Knights Templar criminal organization (Caballeros Templarios, KTO) and the resulting emergence of self-defense organizations (grupos de autodefensas) there since early 2013, the government appointed public security commissioner, Alfredo Castillo, has left his position a year after his installation by the federal government to coordinate security operations there. Castillo has been replaced by Mexican Army General Pedro Felipe Gurrola Ramírez. The move was announced by Interior Minister Miguel Ángel Osorio Chong, and was made in order to shift the focus to the state’s elections, coming up in June. Castillo’s success as Michoacan’s public security commissioner is under debate, with some crediting him with bringing the chaotic situation involving the Knights Templar and the self-defense groups somewhat under control, while others maintain that the underlying problems persist. Speaking with El Universal, several security experts weighed in on the matter, generally agreeing that Castillo’s tenure saw an improvement of the overall security situation in Michoacán, but was not successful in reigning in the self-defense groups. Castillo underwent a campaign beginning early in 2014 to institutionalize the autodefensas, folding them into the state’s security apparatus as part of the Rural Defense Corps. Gerardo Rodríguez, a professor of national security and terrorism and member of the Analysis Collective of Security with Democracy (Colectivo de Análisis de la Seguridad con Democracia, Casede), gives Castillo credit for exposing ties between organized crime and public officials, but said that was the extent of his success, given that he was unable “to articulate a State strategy for fighting a low intensity war,” adding that he also failed to establish meaningful cooperation with local officials. Jorge Chabat, researcher at the Center for Economic Research and Teaching (Centro de Investigación y Docencia Económicas, CIDE), recognized that since Castillo’s instatement a year ago, there have been advancements in the form of fewer criminal groups operating in the open, but that such groups still have not been eliminated entirely. Meanwhile, Sergio Bárcena Juárez, a professor in the judicial and social studies department at Tecnológico Monterrey, said that Castillo “never was able to achieve a sustained and stable treaty, first between the autodefensas and [criminal groups], and later between the autodefensas and the government was very erratic.” Now that many members of the former autodefensas have been incorporated into the Rural Police force in Michoacán, Castillo announced in early January that it would be disbanded for the eventual creation of the Citizens’ Force (Fuerza Ciudadana), which will be Michoacán’s answer to President Enrique Peña Nieto’s call for 32 unified police forces to replace the inconsistent and often corrupt municipal police forces in each Mexican state and the Federal District.

Professor Bárcena Juárez also criticized Castillo for not recognizing the danger of new groups emerging, such as the Viagras. There have been reports recently that the Viagras, a criminal group that, like the predecessors to the Knights Templar, La Familia Michoacana, espouse social goals as their primary motivator, have been eyeing the weakening of the KTO as an opportunity for expanding their own operations. The widest reports have been of the Viagras making their presence known in Apatzingán, the economic center of Michoacán’s troubled Tierra Caliente region, and the former stronghold of the KTO, from which the Viagras are believed to have emerged as a splinter organization. Javier Cortés, general vicar of the Apatzingán diocese, told AFP that the Viagras are quietly waiting for missteps from the government to use to their benefit. Raúl Benítez Manaut, a public security expert at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, UNAM), said that the Viagras “are taking advantage of their connections with paramilitary groups; there is fertile ground for them to be the next bosses of Michoacán.” Jaime Rivera from the Michoacan University (Universidad Michoacana), said that although they do not currently have great operational capacity, they are the strongest armed group to emerge from the downfall of the KTO, and “could represent a new challenge for the State.” An armed confrontation between Federal Police (Policía Federal, PF) and former members of the Rural Forces on January 6 resulting in 44 arrests and nine dead raised concerns that the Viagras had infiltrated that organization. An intelligence report published in Milenio revealed that the former Rural Forces members, who had taken over the Apatzingán municipal building, were under the command of the Viagras. Alfredo Castillo, before leaving his post as public security commissioner, insisted, however, that there was no credible evidence that any members of organized crime had managed to enter into the Rural Forces.

Sources:

“Los Viagras, con los ojos puestos sobre Michoacán.” El Economista. January 19, 2015.

Martínez, Dalia. “Castillo, fuera de Michoacán por elecciones.” El Universal. January 23, 2015.

Jiménez, Eugenia. “Pide AI a PGR continuar con búsqueda de normalistas.” Milenio. January 28, 2015.