Photo: Wikimedia Commons.

06/24/20 (written by kheinle) – A new report finds that Mexico is faring no better in combatting corruption in 2020 than it did in 2019. The report, “The Capacity to Combat Corruption (CCC) Index 2020,” looks at Latin American countries’ capacity and capability to ‘detect, punish, and prevent corruption.’ It does so against the backdrop of the coronavirus pandemic, noting that “in this environment of emergency spending, relaxed controls, and remote working, the risk of corruption and mismanagement of funds has increased.” Roberto Simon, Senior Director of Policy at the Americas Society / Council of the Americas based in New York, and Geert Aalbers, a partner at Control Risks consultancy organization out of London, co-authored the report that published on June 8, 2020.

Corruption at the National and Regional Levels

Of the 15 Latin American countries included in the Capacity to Combat Corruption index, Mexico ranks in the center in the eighth position with an overall score of 4.55 out of 10.00, just slightly slower than its 2019 score of 4.65. Uruguay ranked highest on the list with the most effective means to combat corruption with a score of 7.78. Continuing to face a humanitarian, political, and economic crisis, Venezuela ranked lowest on the list with a 1.52. The scores are based on 14 indicators (e.g., independence of judicial institutions, strength of investigate journalism) and three sub-categories (legal capacity; democracy and political institutions; and civil society, media, and the private sector). Data is collected from a range of international and national sources, including the World Bank and UNESCO, and from surveys conducted by the report’s co-author, Control Risks.

Looking at the three sub-categories, Mexico ranked eighth region-wide in legal capacity with a score of 4.15 out of 10.00. It also ranked eighth in democracy and political institutions (4.55 of 10.00), and sixth in civil society, media, and the private sector (6.24 of 10.00).

AMLO’s Campaign to Combat Corruption

When looking at levels of corruption since 2019, the report summarizes that “not much has changed for Mexico. In fact,” it continues, “the country has stagnated and maintains a poor ability to detect, punish, and prevent corruption.” This highlights the failure of the López Obrador Administration to adequately address corruption despite campaign promises to do so. “One of the most important [factors that explains Mexico’s paralysis] is having not yet advanced long-term institutional reform.” The authors call out several specific concerns.

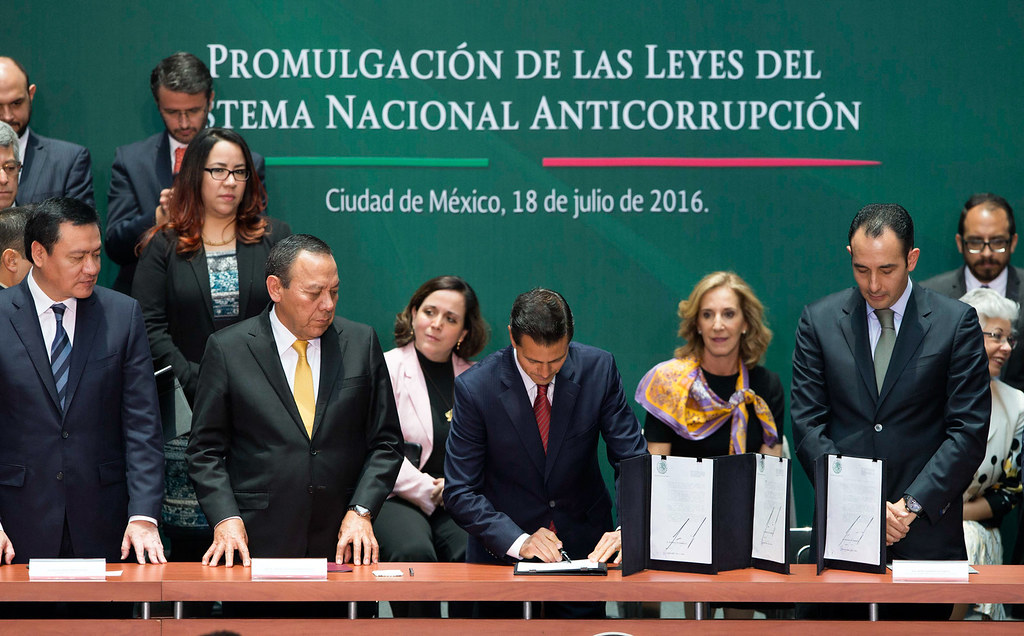

First, President López Obrador has largely bypassed or “ignored” the checks put in place by the National Anticorruption System (Sistema Nacional Anticorrupción, SNA). Second, the president has increased the use of public funds on massive infrastructure projects and on combatting the coronavirus. For its part, the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbates Mexico’s already fraught struggles to combat corruption with the government’s largely unchecked spending amidst real-time, emergency, public health responses. “This combination will only increase the risk of more corruption,” cautions the report.

Third, the president has continued to undermine and diminish the role of nongovernmental organizations and civil society – a sector that had grown more active in recent years in combatting corruption and calling attention to the need for reform. Finally, the nation’s Financial Intelligence Unit (Unidad de Inteligencia Financiera, UFI) has “drastically expanded its activities” in bringing potential cases of corruption against institutions, which ironically has reduced the independence and efficiency of the very anti-corruption agencies that it monitors, writes El Universal. When comparing such independent variables at the regional level, “Mexico appears to be ranked significantly below other countries like Peru, Colombia, and Brazil, and more closely to Guatemala and the Dominican Republic.”

Public Perception and High-Profile Cases

Corruption in Mexico is nothing new. According to Transparency International’s Global Corruption Barometer 2019, 44% of Mexicans interviewed in 2019 thought corruption had increased in the previous 12 months. An additional 34% of respondents had paid a bribe in the previous 12 months, a 10% decline from 2017. When asked if they believe most or all people involved in certain institutions are corrupt, 69% of respondents said police are, 58% said government officials are, and 65% said members of Congress are.

Still, the López Obrador Administration has made some noteworthy investigations into high profile cases of corruption. This includes against the former Secretary of Public Security (Secretaría de Seguridad Pública, SSP), the former CEO of Petróleos Mexicanos (PEMEX), the former head of Altos Hornos de México, and more than a dozen sitting judges and magistrates, including a Supreme Court Justice. Despite these advances, such cases of high-ranking officials and the general presence of corruption throughout Mexico’s government demonstrate just how pervasive and rooted the problem is.